Human smugglers are openly using Facebook to offer migrants passage across the U.S. southern border, according to a new Tech Transparency Project (TTP) investigation that highlights how the social network is contributing to the current border surge.

TTP first noted the presence of human smugglers on Facebook in an April report. Since then, TTP has identified dozens of additional Facebook pages and multiple Facebook groups—with tens of thousands of members—where illegal border crossings are sold.

The human smugglers often show routes, modes of transit, prices, and even discount options to potential customers on Facebook. Many spread misinformation about migrants’ ability to enter the U.S., promising easy and fast asylum. This feeds the false hope on the part of many migrants that they’ll be released by U.S. Border Patrol rather than sent back to Mexico.

TTP also found worrying evidence that some of the smugglers have links to Mexican drug cartels, a sign that larger criminal groups are seeking to capitalize on the migrant surge from Central America—and Facebook’s lax enforcement practices.

The prevalence of human smuggling on Facebook shows the company’s inability, or unwillingness, to identify and deal with dangerous content on its platform, even on a prominent national issue—in this case, the migrant surge at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Here are some highlights from TTP’s new research:

- Dozens of Facebook pages identified by TTP offer illegal border crossings, often featuring videos that show people successfully crossing deserts and rivers into the U.S.

- In private Facebook groups with tens of thousands of members, human smugglers actively sell their services, seeking customers from Central America.

- Human smugglers frequently spread misinformation on Facebook that migrants will have an easy time getting U.S. asylum, fueling misinformation about open borders.

- When presented with a list of 50 human smuggler pages in April, Facebook took down about half, while inexplicably leaving the others up and running.

- Facebook’s push to expand in Latin America through controversial internet-connectivity programs has given human smugglers a massive regional platform to reach would-be migrants.

Prices and routes

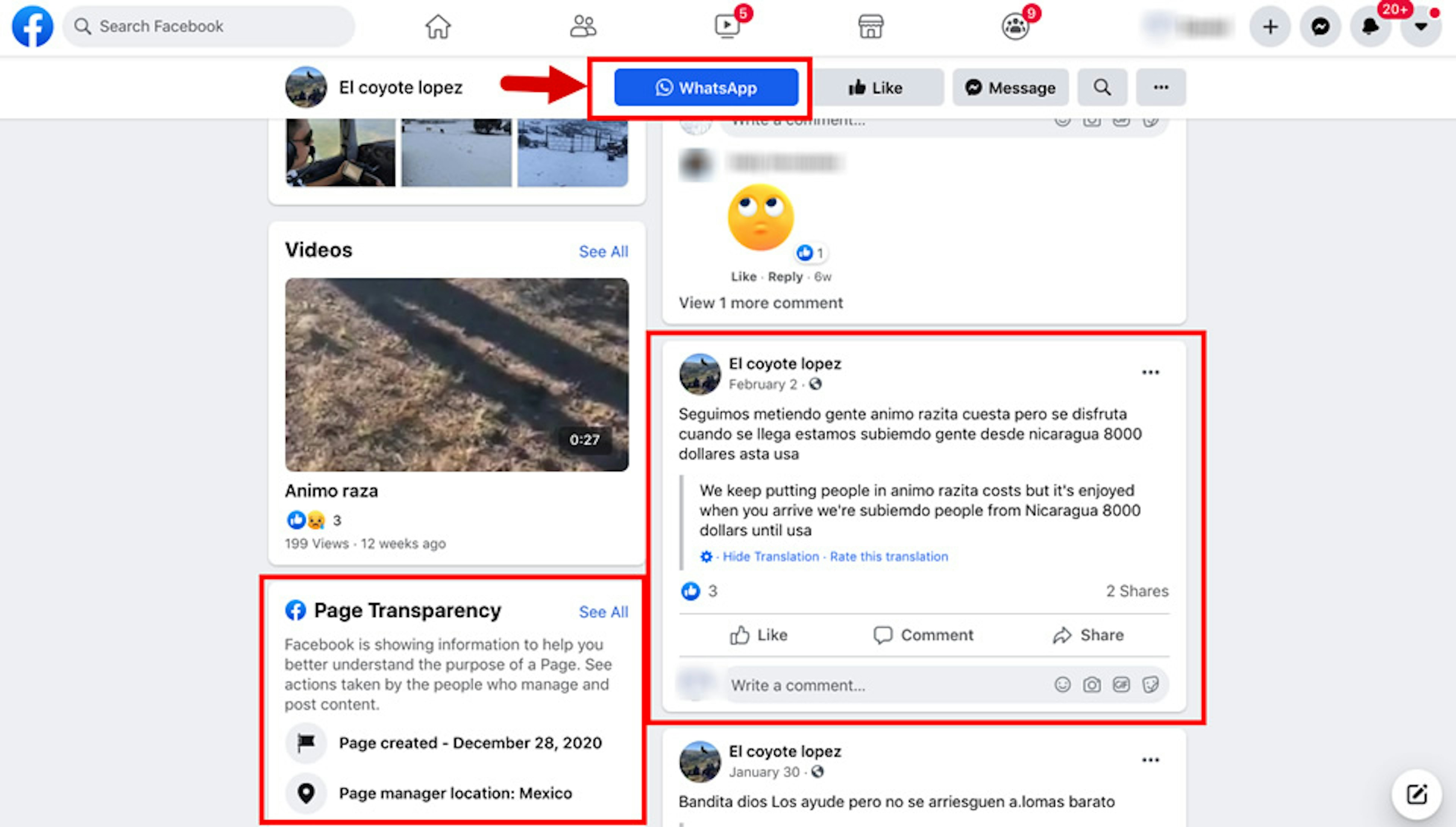

Many of the Facebook smuggler pages identified by TTP did little to disguise themselves or their activity. One page was even called “El coyote lopez” (“The coyote lopez”)—coyote being a commonly used term for human smuggler.

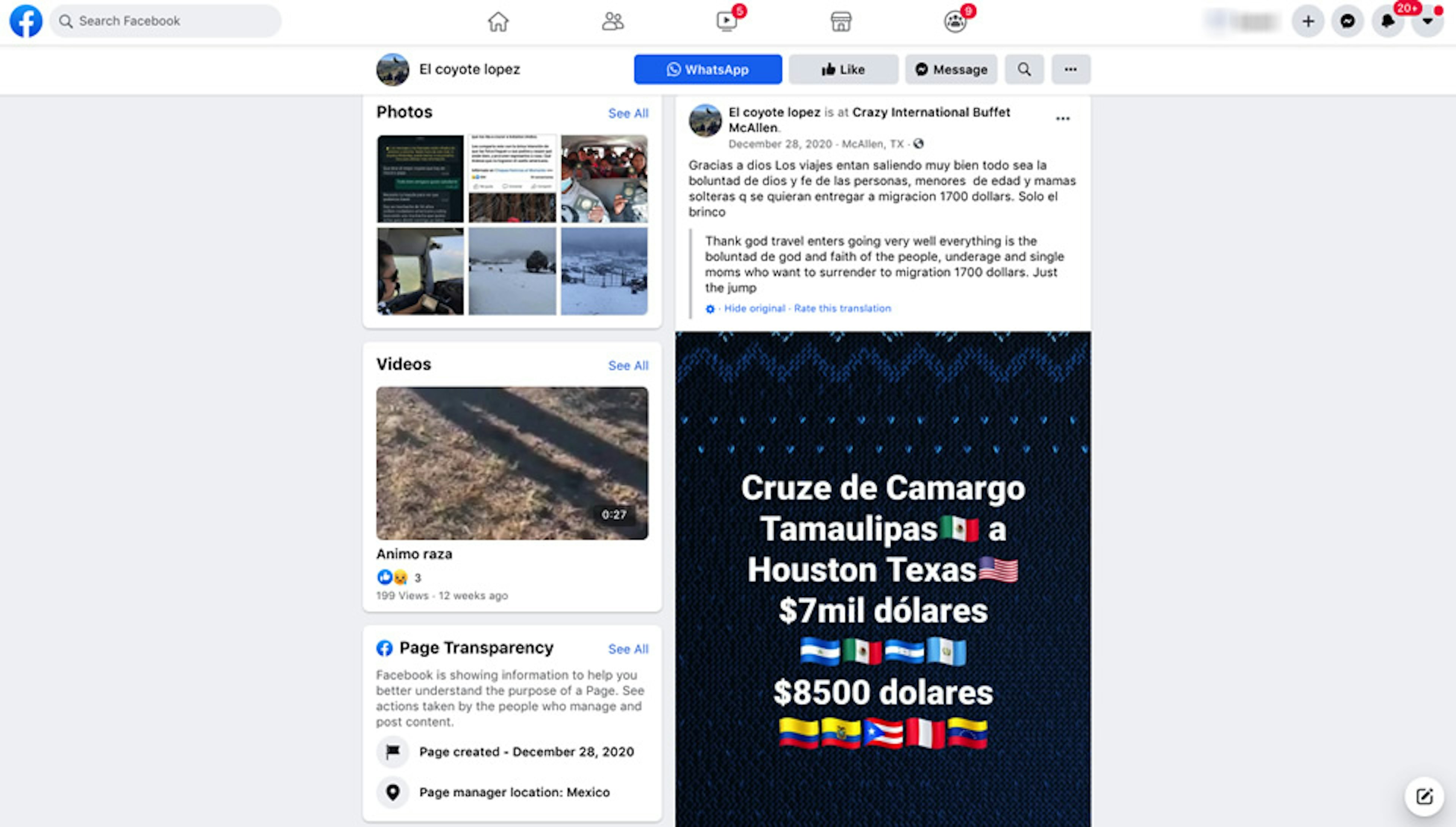

The page, created on Dec. 28, 2020 and managed from Mexico, is explicit about what kinds of services it offers—for example, $8,000 for passage from Nicaragua to the U.S. The page has a WhatsApp button that allows users to connect directly to the human smugglers behind the operation.

One El coyote lopez post tagged in the border city of McAllen, Texas, highlighted its success and offered a discount rate of $1,700 for single mothers and children willing to hand themselves over to a Border Patrol agent when they reach the U.S. The post indicates a more expensive rate of $7,000 to $8,500 for passage all the way to Houston, and uses flag emojis to indicate it takes migrants from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua.

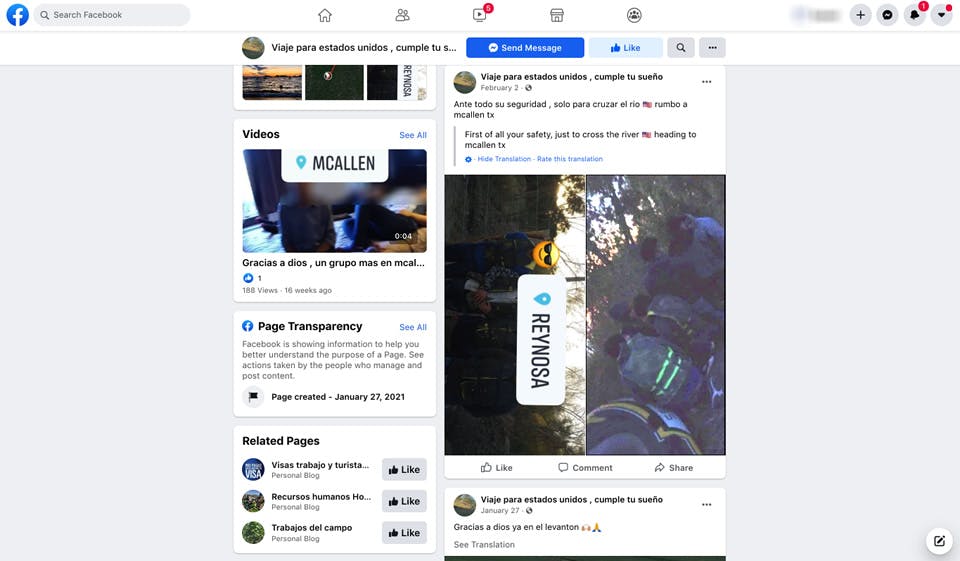

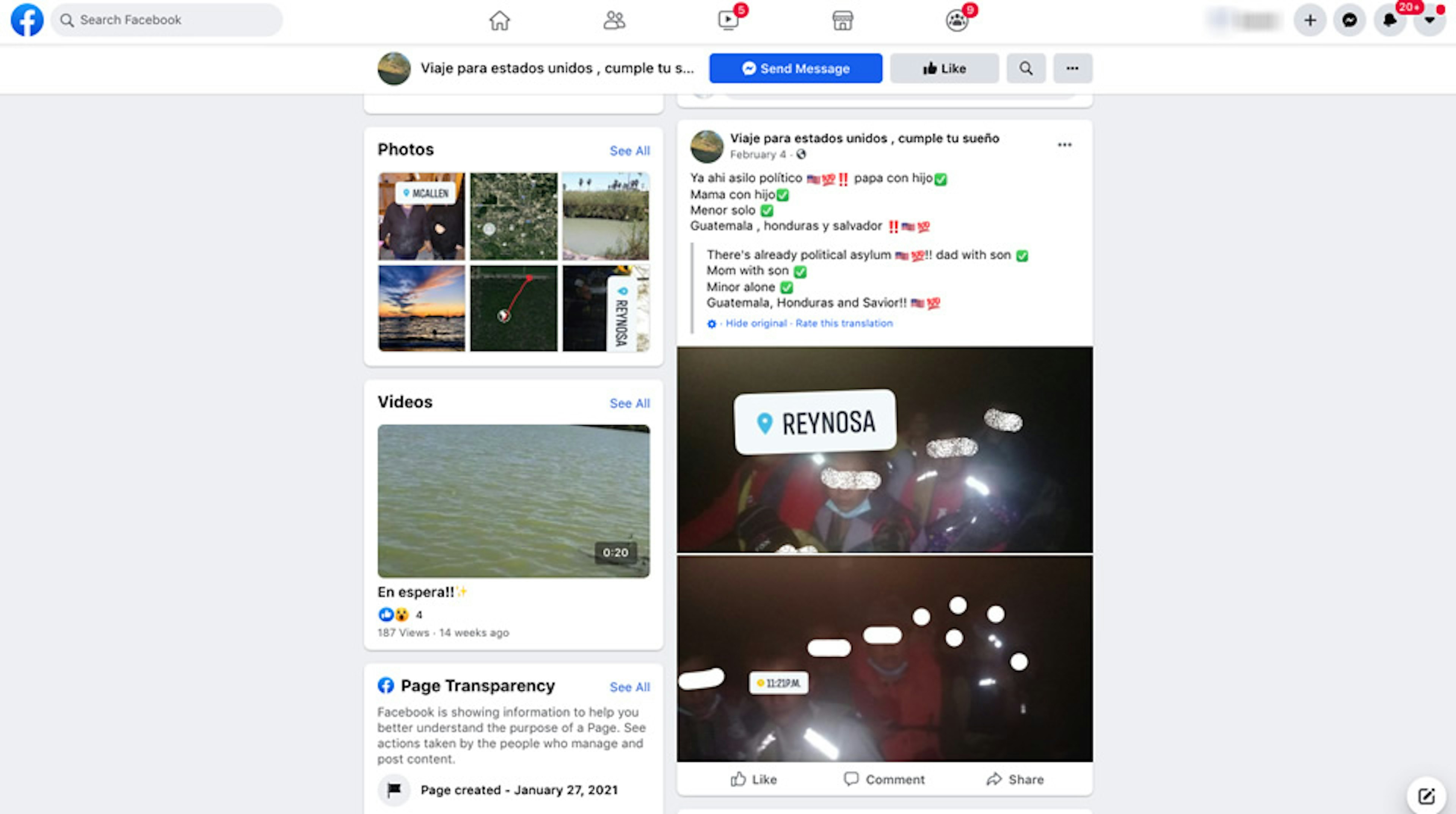

Another Facebook page called “Viaje para estados unidos , cumple tu sueño” (“Travel to the United States, fulfill your dream”), created on Jan. 27, 2021, offers passage from Reynosa, Mexico, across the border to McAllen, Texas, with video of people on a raft reaching a riverbank and crawling ashore through tall grass.

The page talks up its focus on client “safety,” showing photos of people wearing life vests. Human smugglers frequently post photos and videos of migrants during their journey to instill confidence that the smuggler is not simply an online scammer.

Cartel connections

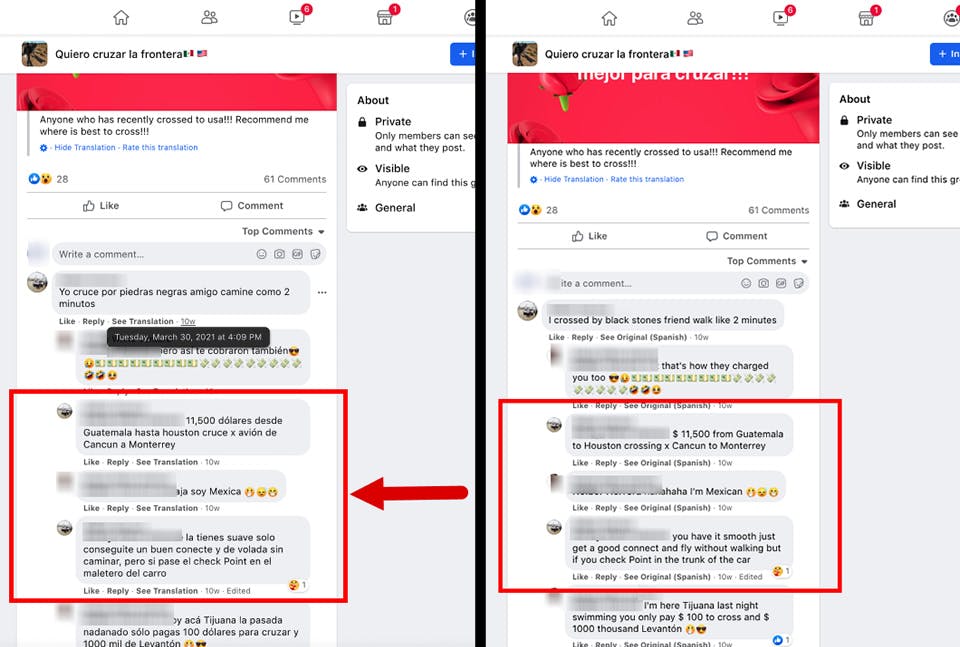

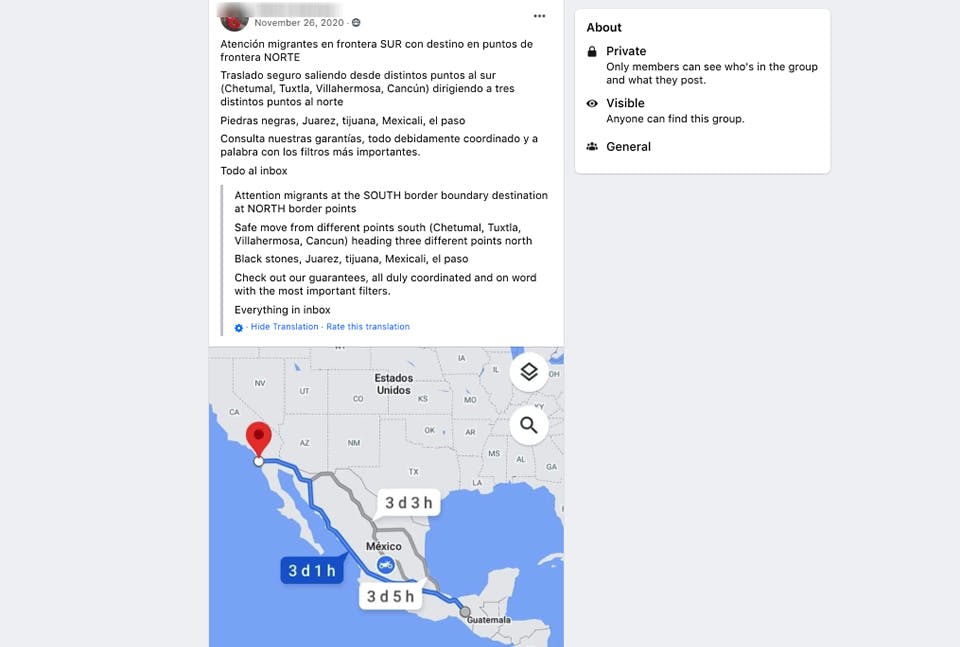

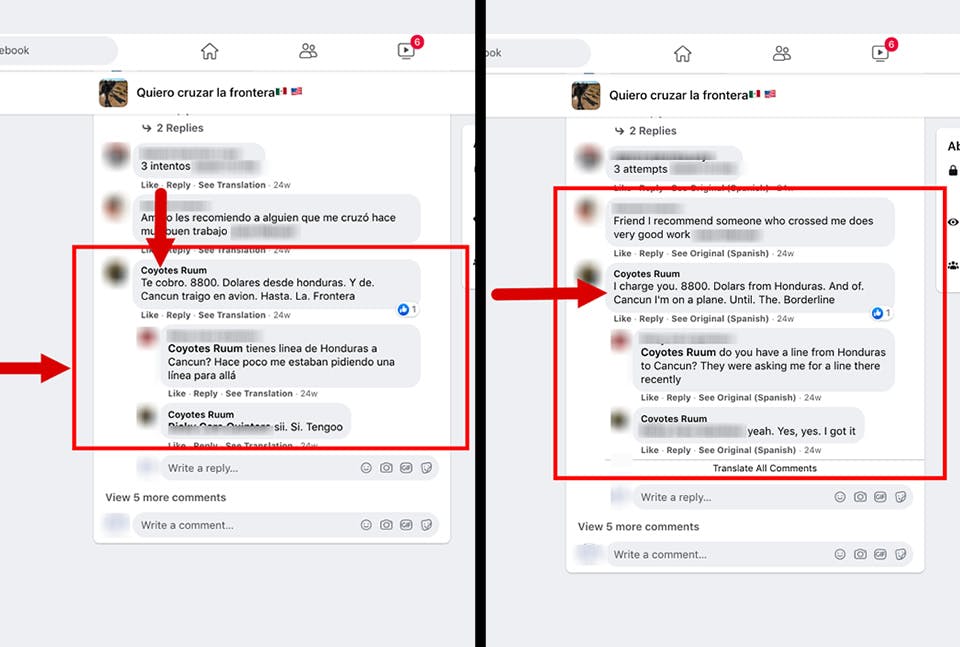

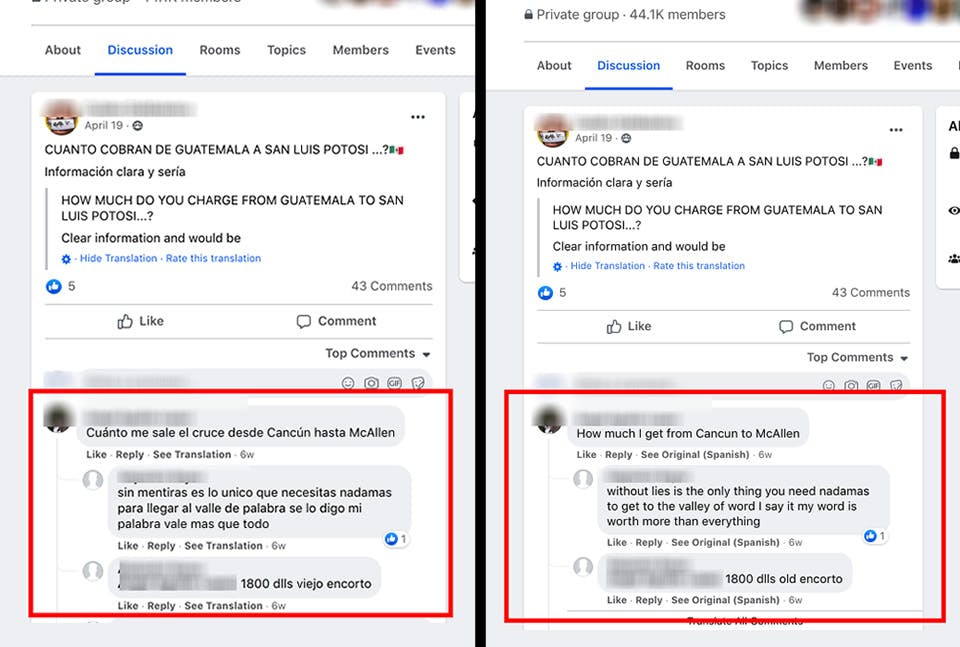

TTP also identified several private Facebook groups that are hotbeds for the sale of illegal border crossings. Inside these groups, which have tens of thousands of members, human smugglers actively promote their services.

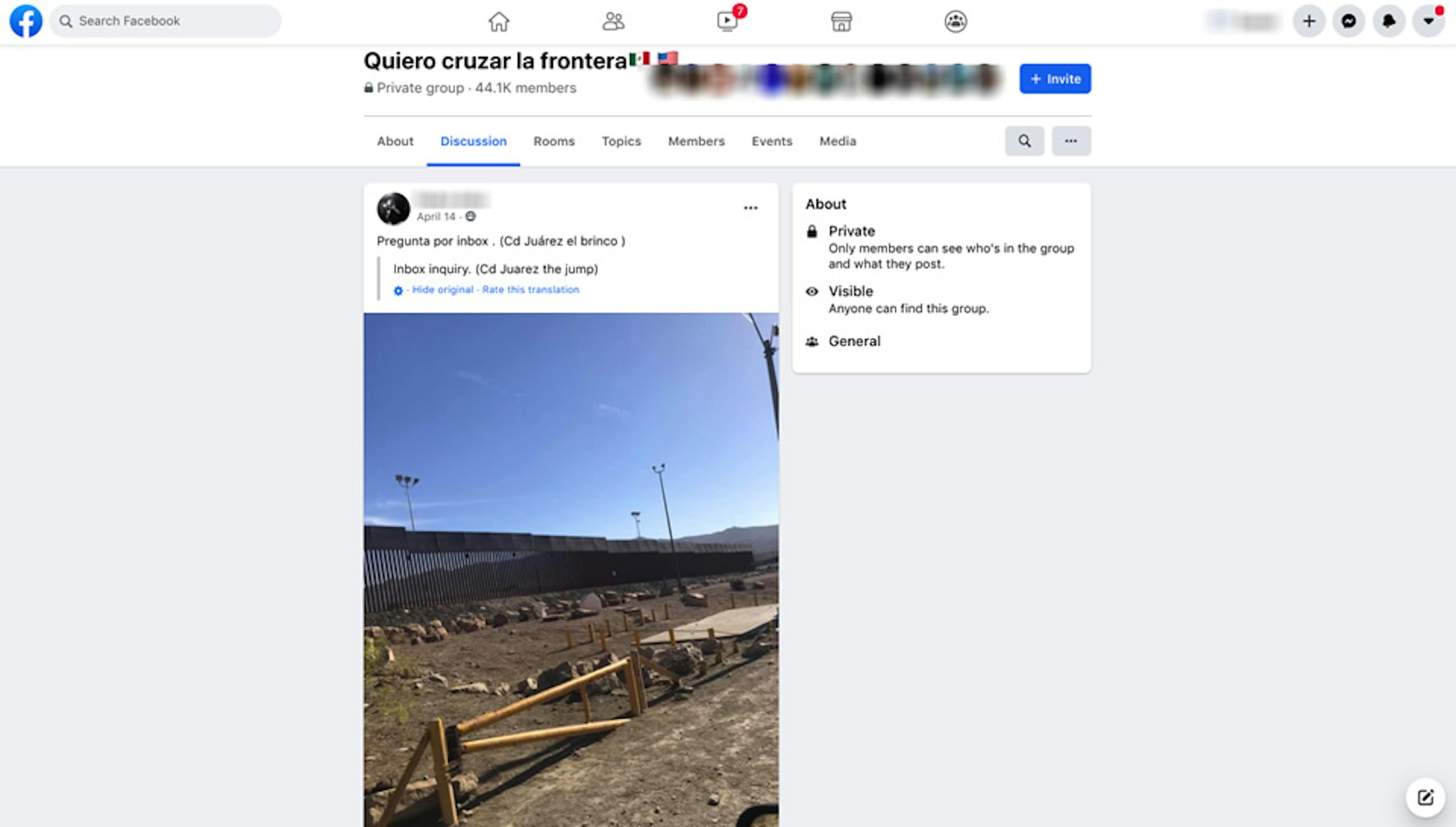

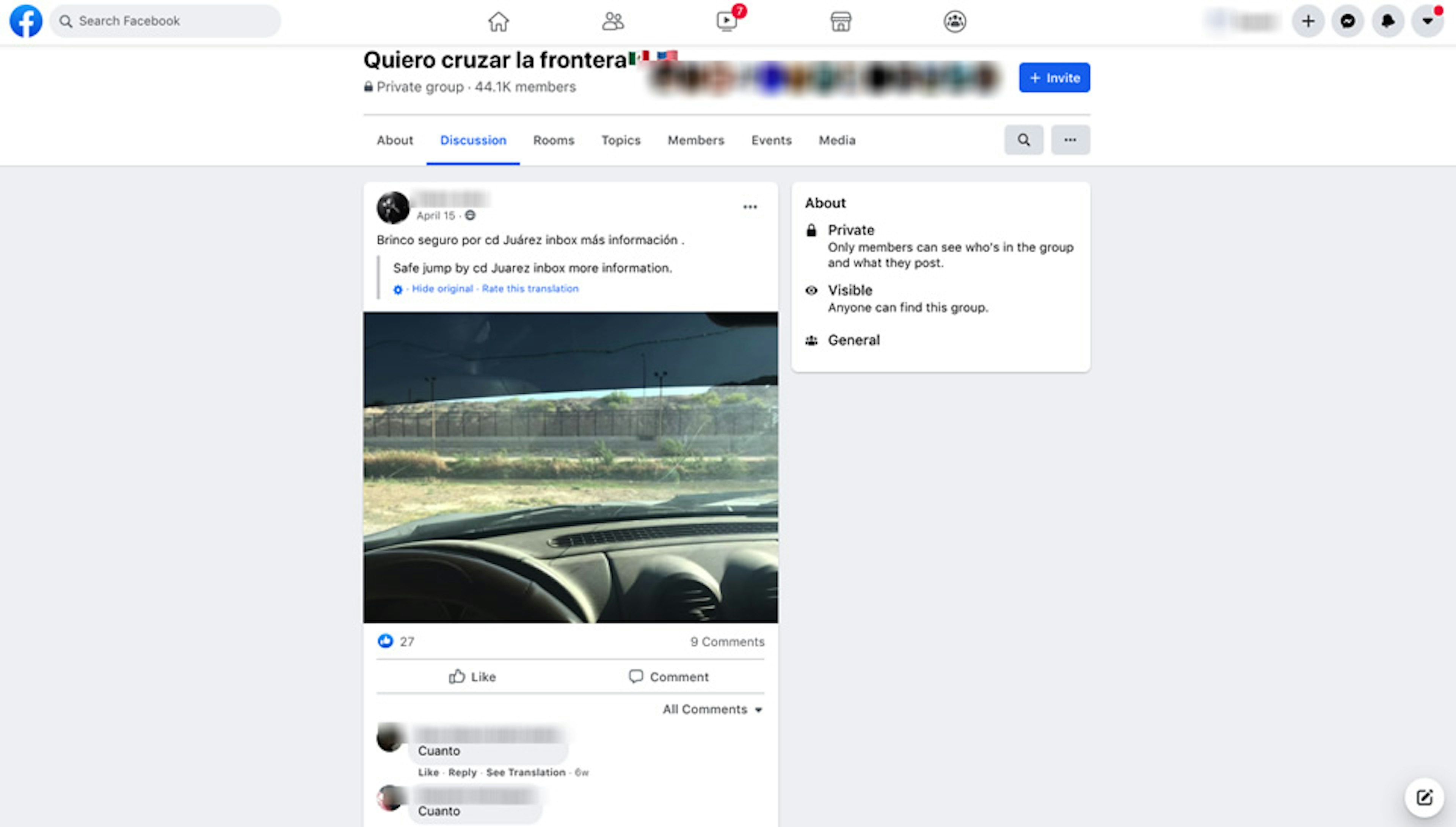

For example, in a 44,000-member Facebook group called “Quiero cruzar la frontera [US and Mexican flag emojis]” (“I want to cross the border”), one user has spent weeks posting videos that amount to a travelogue, illustrating the routes he’s taking migrants on their way to the U.S. The videos show people walking and sleeping in desert terrain and scaling what appears to be a border wall. On May 23, 2021, he encouraged users interested in crossing the border to privately message him, saying the full cost is due once the trip is completed in Phoenix, Arizona.

According to Dr. Nilda Garcia, a researcher specializing in cartel activity on social networks, this same user exhibited signs of cartel affiliation. Based on the user’s rhetoric and the types of weapons he displays, it appears that he is a lower ranking cartel member, such as a “halcon.” The user’s stated location in Agua Prieta in the Mexican state of Sonora suggests a connection with the Sinaloa cartel’s Gente Nueva or Los Salazar cells, which dominate the border zones between Sonora and Arizona.

TTP worked with Dr. Garcia in analyzing some of the Facebook content highlighted in this report.

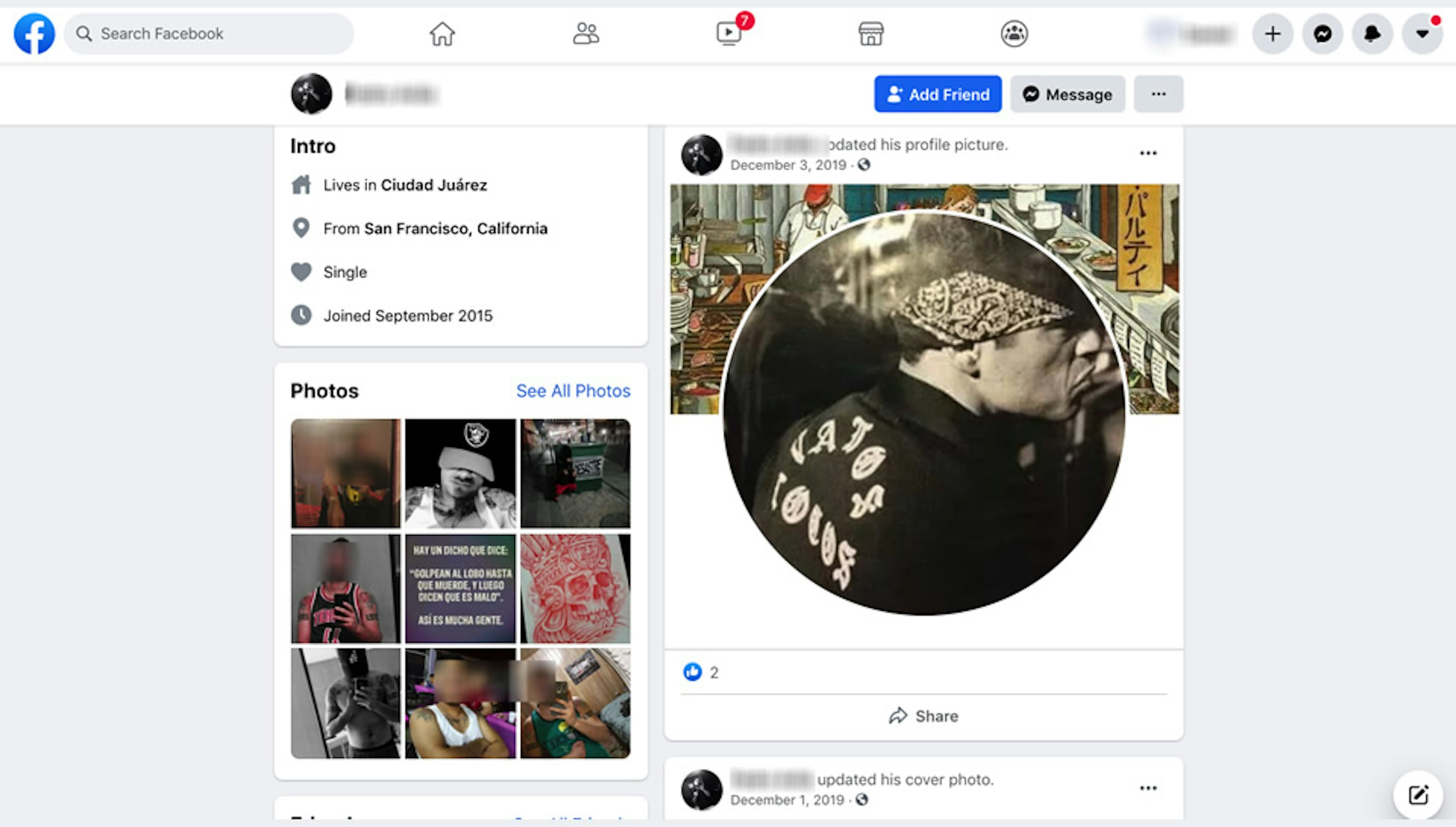

Another user in the “Quiero cruzar la frontera” Facebook group offers smuggling services, photos of border wall, and a video of a group of people in the desert, with one person’s face hidden by an emoji. The user’s profile photos include gang logos and hand signs associated with Vatos Locos, a criminal gang that operates in Mexico and other Latin American countries and has ties to Mexican drug cartels.

TTP also found examples of smugglers, when listing their border crossing prices, tacking on a fee of up to $700 per person that’s paid to cartels when crossing their territory. This right-of-way tax is often referred to as “cobro de piso,” and groups who don’t pay it run the risk of extortion, kidnapping, or death. The smuggler Facebook accounts that mentioned this fee come from the Mexican border states of Tamaulipas, Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Baja California.

For cartels, particularly those operating in northern Mexico, human smuggling has become a lucrative business, as they capitalize on the surging demand from migrants looking to enter the U.S. These criminal organizations are known to make heavy use of social media to burnish their reputations, incite fear, and recruit new members.

Below are some other examples of Facebook activity identified by TTP and Dr. Garcia that suggest cartel associations.

False rumors

TTP also found posts by human smugglers full of promises that the Biden administration is throwing open the southern border to migrants. One post included images of people in a raft at night with text that suggests people are easily getting asylum, a common piece of misinformation that’s fueling the current border surge.

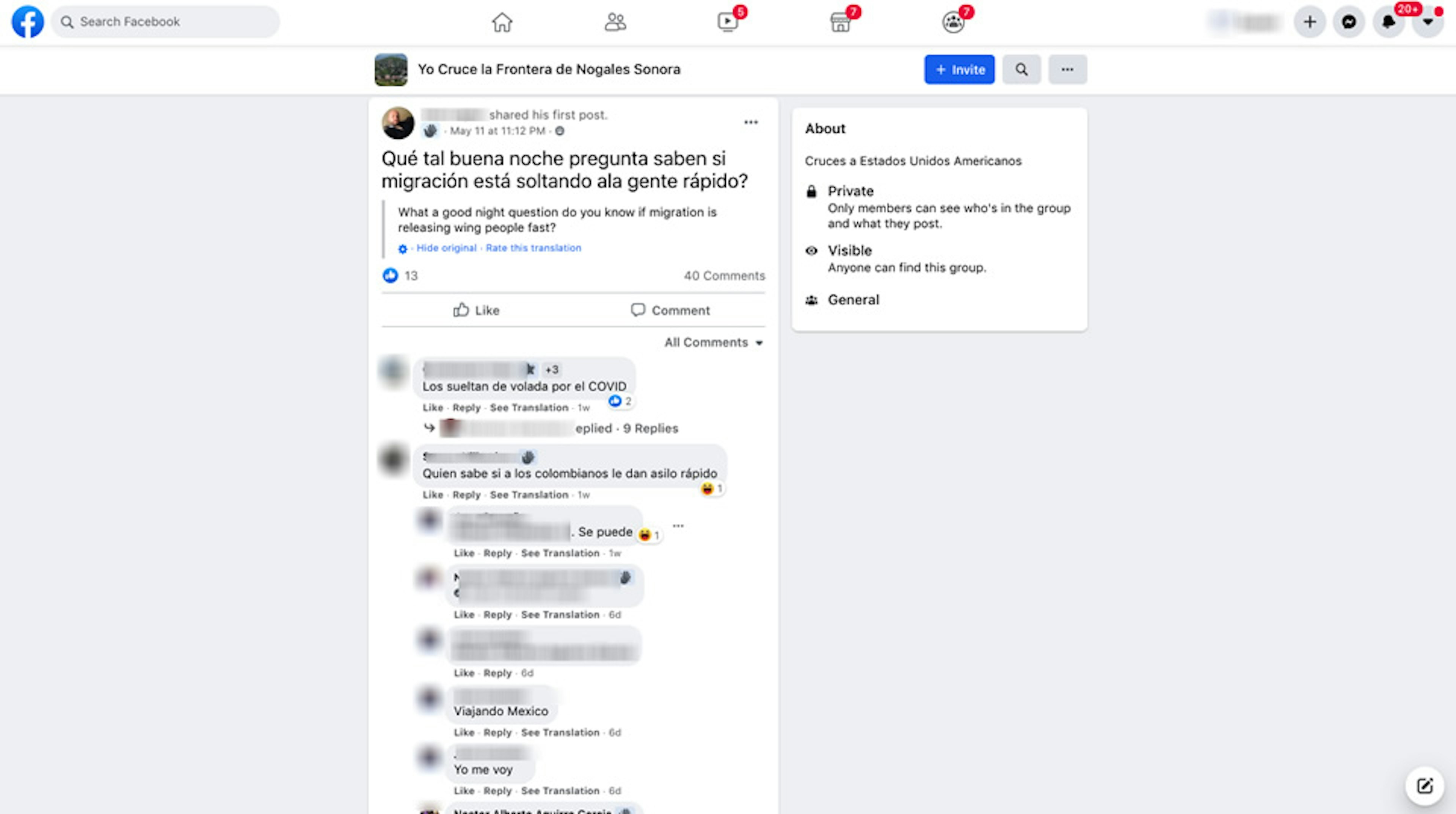

Such misinformation is also present in Facebook groups where human smugglers sell their services. In an 11,000-member group created on April 14, 2021, called “Yo Cruce la Frontera de Nogales Sonora” (“I Cross the Nogales Sonora Border”), a user asks if U.S. Border Patrol is releasing migrants quickly due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Another person replies that the user can get quick asylum as a Colombian—and then seizes the opportunity to offer passage to Mexico.

In one Facebook group, human smugglers have spent months offering passage to the U.S. via Cancun, Mexico. Several of the posts identified by TTP specifically targeted Guatemalan and Honduran migrants. U.S. officials have become aware of migrants arriving in Cancun under the guise of tourism on their way to the U.S. southern border, according to a CNN report, which said U.S. border agents have been deployed to work with Mexican authorities on the issue.

TTP’s findings reveal multiple violations of Facebook’s own policies—sometimes in a single post. Facebook's Community Standards ban “misinformation and unverifiable rumors that contribute to the risk of imminent violence or physical harm.” They also explicitly ban content that “offers to provide or facilitate human smuggling.”

The Biden administration has worked to dispel false rumors about open borders. Speaking about the migrant crisis in February, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki told reporters, “Now is not the time to come. The vast majority of people will be turned away. Asylum processes at the border will not occur immediately, will take time to implement."

In March, the administration launched a social media campaign—including advertising on Facebook and Facebook-owned Instagram—to convince people in Central America not to enter the U.S. Meanwhile, Vice President Kamala Harris, on a visit to Guatemala this week, drove home the message: "I want to be clear to folks in this region who are thinking about making that dangerous trek to the United States-Mexico border: Do not come. Do not come."

But the effort faces an uphill battle when Facebook, whose platforms are among the most widely used in Latin America, is failing to do its part in combatting misinformation and deterring people smugglers.

Enforcement fails

TTP’s previous April investigation identified 50 Facebook pages and multiple private Facebook groups offering illegal border crossing, simply by searching for basic Spanish phrases like “viajar a estados Unidos” (“travel to the United States”) and “cruzando a estados Unidos” (“cross to the United States”). Following that report, Facebook reached out to TTP to request a list of those pages and groups, which TTP provided.

Rep. Kat Cammack (R-Fla.), a member of the House Homeland Security Committee, highlighted TTP’s findings in a May 5 letter to CEO Mark Zuckerberg, noting that Facebook has become a vehicle for “spreading false information and openly advertising illicit smuggling services.” Cammack said U.S. border agents in Texas had told her that cartels and human smugglers use Facebook to post paid advertisements for illegal border crossings, and said she heard from migrants who used Facebook to arrange payments and logistical details for such crossings.

In response to a Daily Mail report on Cammack’s letter, Facebook said in a statement, “We prohibit content that either offers or assists with human smuggling. We have removed the content highlighted to us that violates our policies.” But a month after Facebook received TTP’s list of human smuggling content, nearly half of the identified pages (19) remained active on the platform.

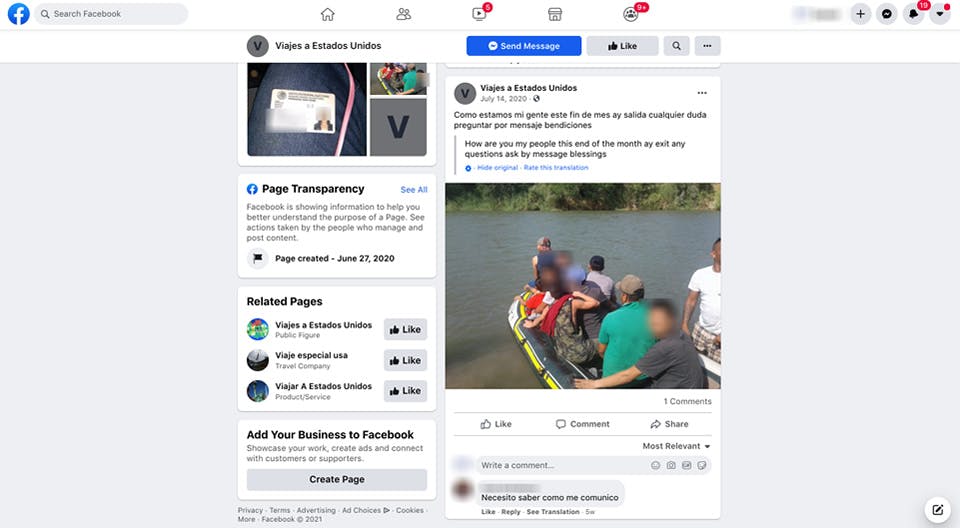

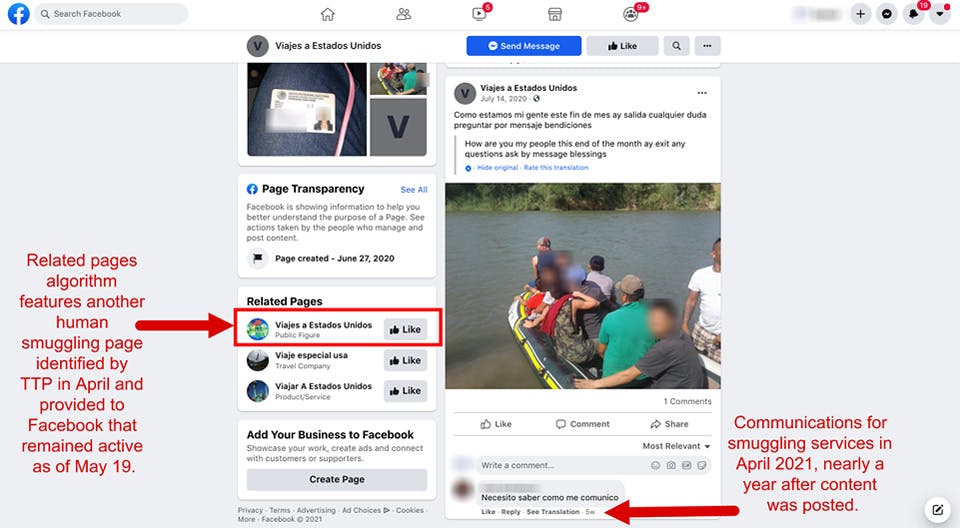

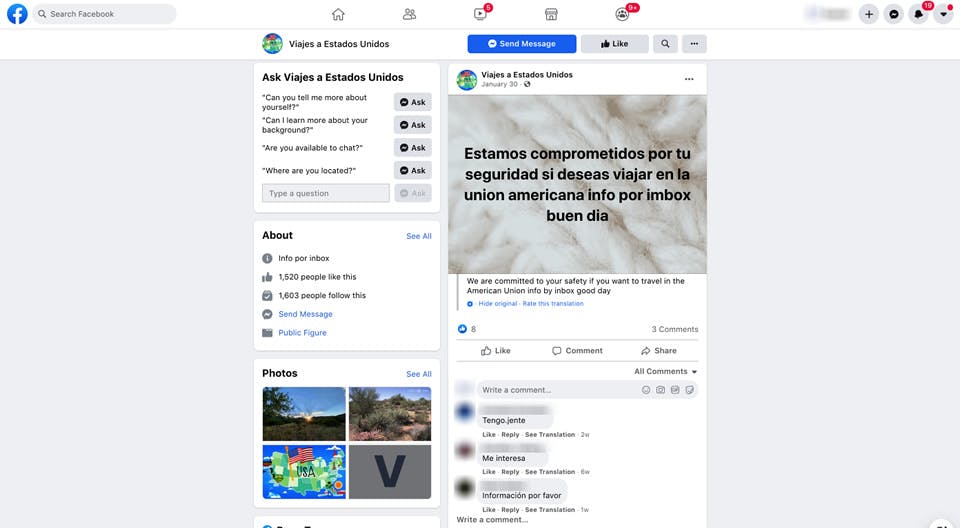

Those pages include “Viajes a Estados Unidos” (“Travel to the United States”), which features posts offering illegal crossings and a photo of adults and children packed into a raft heading toward a riverbank. The page is still receiving messages from interested users nearly a year it was created. (Human smuggling pages often use names that mimic legitimate travel and visa services.)

Facebook frequently amplifies this content through its automatic features.

For example, on the “Viajes a Estados Unidos” page, Facebook’s algorithmically driven “Related Pages” feature recommended another human smuggling page with the same name, which TTP had also flagged in its April list. The recommended page includes posts offering safe passage to the U.S. alongside photos of the desert.

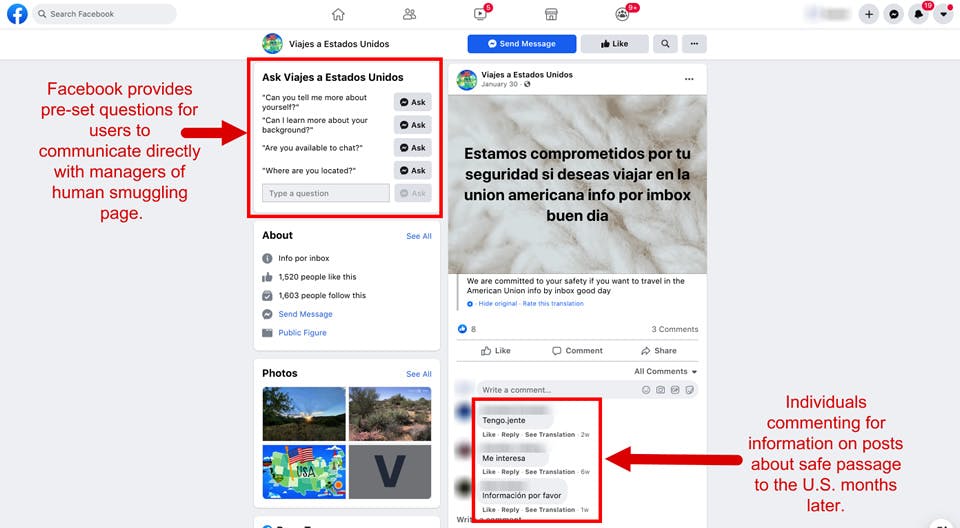

Visitors to these pages often get served a Facebook pop-up messenger window, complete with pre-set questions like “Are you available to chat?” This provides an easy way for people to privately contact human smugglers with a single click.

It’s not clear why Facebook has not removed these remaining pages despite clear content offering human smuggling services.

Latin America push

Facebook has in many ways become a one-stop shop for human smugglers, allowing them to identify, solicit, and privately communicate with would-be migrants. That’s not a coincidence: Facebook has used controversial internet-connectivity programs to make itself ubiquitous in Latin America, while struggling to effectively police its platform.

As Facebook’s penetration of U.S. and European markets plateaued, the company turned its attention to another growth opportunity: regions with poor internet access. In 2013, Facebook launched its Internet.org initiative (later rebranded as Free Basics), described as an effort to bring more of the developing world online. Under the program, Facebook partnered with local wireless carriers to offer a limited set of applications—including Facebook—through so-called zero-rating, in which people get access to specific internet apps without incurring data charges.

The stated goal was to bring internet access to underserved parts of the world, but the program quickly faced a backlash over concerns that it threatened to turn the internet into a “walled garden” of Facebook-approved applications. Digital activists expressed particular alarm about the program’s expansion in Latin America. The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) warned in 2015 that Internet.org could replace the “real internet” in countries like Colombia, Brazil, and Peru.

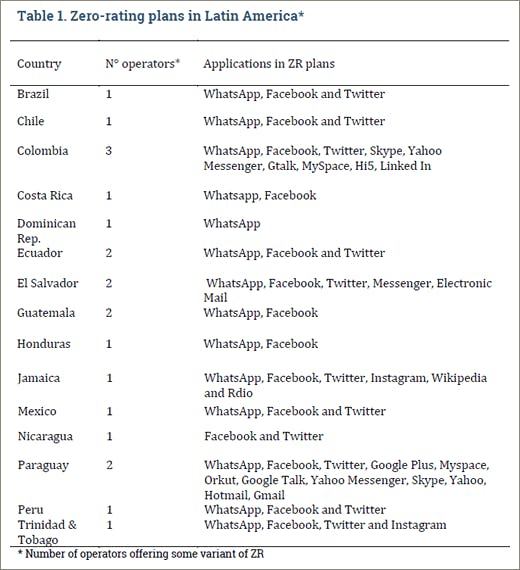

A 2016 study tallied 15 zero-rating plans in Latin America and the Caribbean that offered Facebook and/or Facebook-owned WhatsApp as part of their offerings.

By the following year, at least 15 Latin American and Caribbean countries had some variation of zero-rating services, all of them offering Facebook, Facebook-owned WhatsApp, or both, according to one study. In Guatemala, Honduras, and Costa Rica, Facebook and WhatsApp were the only applications offered in these zero-rating plans. In essence, Facebook positioned itself to be the internet in Latin America.

Facebook doesn’t break out user metrics for Latin America in its annual reports—instead lumping the region into a “rest of the world” category with Africa, the Middle East, and other regions. Facebook’s monthly active users in the “rest of the world” increased from 436 million in December 2014 to 921 million in December 2020, according to company figures. That took Facebook’s worldwide user base from 1.39 billion to 2.8 billion over the same period.

Facebook’s rapid expansion in Latin America—fueled by controversial zero-rating arrangements—and its struggles to remove dangerous content have been a boon to human smugglers, who can use Facebook’s massive platform to reach new customers instead of relying on local word-of-mouth to drum up business.

P.R. rinse, repeat

Facebook’s human smuggling problem is in many ways a global phenomenon.

In recent years, media reports have documented how smugglers have used Facebook to lure migrants into everything from dangerous Mediterranean Sea crossings to illegal labor transfers from Vietnam to the United Kingdom. In 2017, a spokesman for the United Nation's International Organization for Migration (IOM) said Facebook had created "a turbocharged communication channel to criminals, smugglers, traffickers and exploiters."

Despite this longstanding, well-documented issue, Facebook hasn’t made discernible progress in tackling the problem. And when reports over the years have highlighted instances of human smuggling on Facebook, in a variety of countries and contexts, the company has used remarkably similar language in its public relations statements—saying the activity violates Facebook policy and encouraging users to report abuses, without addressing Facebook’s own responsibility for policing its platform.

You can see this pattern in the interactive graphic below:

Contributor note: Nilda M. Garcia is an assistant professor in the Political Science Department at Texas A&M International University and a member of the Alliance to Counter Crime Online. Dr. Garcia received her PhD in International Studies from the University of Miami in 2018 with a concentration in International Relations Theory and International Political Economy. She also holds an MBA in International Trade and a BA in Business Administration from Texas A&M International University. Her research focus includes organized crime, drug trafficking, international relations, and security studies.