In 2018, Google spent the most of any U.S. corporation on lobbying Washington, D.C., devoting more than $21 million to influencing policymakers from Congress to the executive branch. The company’s growing D.C. operation had begun to attract media attention, undermining its self-image as an altruistic company above politics, epitomized by its early motto, “Don’t Be Evil”.

Then, Google suddenly dropped off the list of top corporate lobbying spenders, its total outlays falling by two-thirds over the next two years. The company’s decision to fire multiple outside lobbying firms, which made headlines in June 2019, was one factor in the decline.

But there was more to the story. The Tech Transparency Project (TTP) has discovered that Google also employed a little-known legal strategy that removed lobbying by its executives from the disclosures it files under federal law.

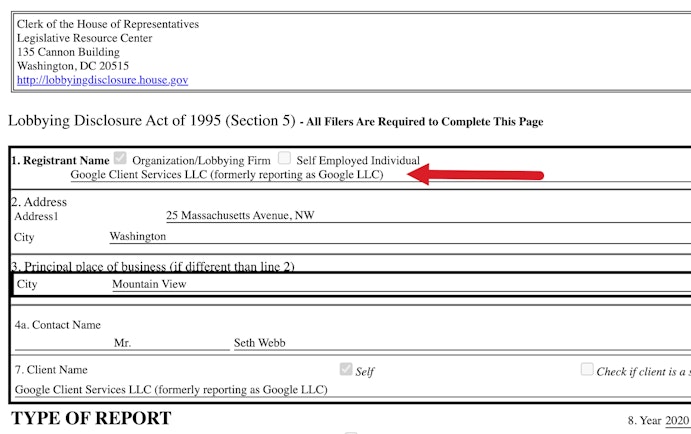

For most of its existence, Google included the value of any lobbying by its senior executives in its disclosures, as most companies do. In early 2020, however, Google quietly moved its in-house lobbyists into a new subsidiary it called Google Client Services LLC.

Now that Google’s parent company had no in-house lobbyists, the company reasoned, it no longer had to register at all, according to current and former Google employees. And, because Google’s executives didn’t technically work for the lobbying subsidiary, they wouldn’t have to disclose the cost of their lobbying, either. The employees asked not to be named to discuss the company’s internal deliberations.

Under the new model, Google’s lobbying expenses fell by millions of dollars, and it dropped out of the top 20 corporate lobbying spenders for the first time in nearly a decade.

In a statement, Google said there were multiple reasons behind the decrease in the company’s lobbying numbers, including a restructuring of the company’s government affairs operation and the pandemic. Google called the creation of the subsidiary “a technical change that aligns with how other companies report and fully complies with disclosure laws.”

But a longtime expert on the Lobbying Disclosure Act (LDA) questioned Google’s move to keep executive lobbying under wraps. “This is just a shell game that the Act doesn’t permit,” said William Luneburg Jr., a University of Pittsburgh law professor who co-edited a comprehensive lobbying manual published by the American Bar Association.

Luneburg said that because the subsidiary is directed by Google and only lobbies on issues that affect Google, it should file consolidated disclosure reports covering employees of both units. He said it’s problematic that the Google subsidiary lists its “client” as itself, not Google.

“They are not lobbying on their own behalf—they are lobbying on issues for Google,” Luneburg said. “They can’t have it both ways.”

Google’s arrangement, which has not previously been reported, has allowed the company to shield a significant portion of its lobbying expenditures from public view. With Big Tech executives like Google CEO Sundar Pichai playing a bigger role in advocating for their companies, Google’s arrangement means that the public will be kept in the dark about the full scope of its lobbying operation.

Subsidiary model

Lobbying lawyers interviewed by TTP said they knew of a handful of other companies that have created similar lobbying subsidiaries, but said they generally did so to consolidate corporate lobbying activity to make it easier to calculate expenses. They were not aware of a company using this model to remove executive lobbying from its disclosures.

TTP examined the lobbying reports of several companies that, like Google, have changed their lobbying registration to something with “services” in the name, but none showed any significant decrease in lobbying expenses after they started filing under the new entity.

Google declined to specify the amount of executive lobbying expenses that have gone unreported by the company as a result of its subsidiary arrangement, but the impact of removing top executives like CEO Sundar Pichai from the disclosures appears significant.

Take a hypothetical example involving Pichai. If an executive works for a company that has an in-house lobbyist and spends time lobbying members of Congress, White House aides, or Cabinet-level officials, the company should disclose the portion of the executive’s “salary and benefit costs” covering that time, plus associated travel and overhead, according to legal guidance from congressional officials.

“If you have your CEO spend a couple of days on Capitol Hill, you have to report the expenses on your LDA report,” said Matthew Sanderson of the law firm Caplin & Drysdale.

Google reported Pichai’s 2022 compensation as nearly $226 million. That includes stock awards, which are considered part of an executive’s pay when calculating their lobbying expenses, lobbying law attorneys told TTP.

“If compensation includes other forms aside of salary, like stock options, they have to capture that pro rata portion on their reports,” said Jan Baran, an attorney who advises clients on lobbying issues for the law firm Holtzman Vogel.

By that measure, Google would have been required to disclose at least $4.3 million for a week of Pichai’s lobbying activity in 2022. Under Google’s subsidiary arrangement, however, the company would have disclosed none of that.

Google CEO Sundar Pichai at an artificial intelligence forum on Capitol Hill in September 2023.

Numbers go up, then down

Google hired its first lobbyists in Washington in 2003 and soon after tapped an MIT-educated engineer, Alan Davidson, to run its D.C. office. Davidson spent much of his time talking with policymakers about the wonders of the internet.

But Google soon saw a need to scale up its influence activities as telecom and media giants like AT&T, Comcast, and News Corp. began to view the search engine as a threat. Google formed its first political action committee in 2006 and hired scores of lobbyists with connections to both parties on Capitol Hill.

A pivot point came in 2011 when the Federal Trade Commission opened an investigation into whether Google operated an illegal monopoly. Just days after the investigation became public, Google hired 12 new lobbying firms.

The FTC eventually ended its antitrust investigation of Google without taking action against the company. (It later emerged that the FTC’s Bureau of Competition had concluded that Google was indeed a monopoly and recommended an antitrust lawsuit, but the agency’s commissioners did not follow that advice.)

Google’s newfound lobbying muscle produced wins on copyright, privacy, and other issues. From 2012 to 2018, Google was among the nation’s top corporate spenders on lobbying and ranked No. 1 in three of those years.

The company’s influence operation also brought unflattering media attention. News reports frequently remarked on Google’s status as a corporate heavyweight in D.C.—a far cry from its early days as an idealistic upstart.

In 2019, Google reversed course on its years of lobbying growth by dumping a slew of outside lobbying firms. One news report quoted sources familiar with the matter who called it a “modernization” of the company’s influence operation. (Filings show Google dropped 12 lobby firms in total.)

Google’s disclosed lobbying expenses began to fall during this period, dropping from a record high of $21.2 million in 2018 to $11.8 million in 2019 to $7.5 million in 2020—a decline of $13.7 million, or 65%. The company slid down the ranks of top corporate lobbying spenders, and many media outlets shifted their focus to lobbying by tech giants Facebook and Amazon.

But TTP’s investigation found that Google’s decline in lobby spending during this period could not be solely explained by its shedding of the 12 outside lobby firms, which were paid a total of $1.8 million in 2018. In fact, much of decline coincided with Google’s creation of the lobbying subsidiary, Google Client Services LLC.

In early 2020, Google moved its in-house lobbyists into a new subsidiary it called Google Client Services LLC.

Google’s disclosures indicate that it shifted its lobbying operation to Google Client Services in the first quarter of 2020. During the previous quarter, Google reported spending $2.74 million on lobbying. But in the first quarter of 2020, under the new lobbying subsidiary, Google’s lobbying expenses fell to $1.8 million, a 34% drop.

Using a year-over-year comparison, Google’s $1.8 million lobbying tab in the first quarter of 2020 represented a 46% drop from the same quarter in 2019 ($3.36 million).

Once the lobbyists were moved to the subsidiary, no one left at the main company Google was spending more than 20% of their time on lobbying. Having at least one employee spend 20% of their time on lobbying is one of the legal triggers requiring a company to file a lobbying registration, make monthly disclosure reports, and list the lobbying expenses of executives, according to the guidance from congressional officials. Google stopped disclosing executive lobbying activity under the new subsidiary arrangement.

This decline in lobbying numbers was a win-win for Google. Not only did the company receive less media attention for its spending on lobbyists, but the media also focused more on the influence efforts of its tech rivals Facebook and Amazon.

Since 2020, Google’s disclosed lobbying spending has crept back upward, reaching $12.3 million last year, though it is still well below its peak levels.

Brody Mullins, co-author of “The Wolves of K Street: The Secret History of How Big Money Took Over Big Government,” contributed to this report.