The Supreme Court ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade has focused attention on the ways in which tech companies collect vast amounts of data on users—data that could be tapped by law enforcement officials in states where abortion becomes criminalized, or anyone else intent on tracking someone seeking an abortion.

A new investigation by the Tech Transparency Project (TTP) shows how Google’s own technology allows unwanted surveillance that can expose a user’s location, creating risks for abortion seekers, victims of domestic abuse or stalking, and others who want to protect their privacy. This loophole could expose highly sensitive personal information to abusive partners, parents, or employers.

Through a series of experiments, TTP found that an Android phone associated with one Google account can easily access and view the location history of another account, tracking physical movements like a visit to an abortion clinic, even when the second user’s location history is turned off.

The findings raise new questions about Google’s approach to user privacy. Despite banning so-called stalkerware apps that are used for spying on others without their consent, Google has baked-in technology that provides the same surveillance capabilities.

Following the Supreme Court’s June 2022 decision overturning the constitutional right to an abortion, Google announced on July 1 that it would delete places like abortion clinics and domestic violence shelters from users’ location histories “soon after” they visit those locations. Google gave no specific timeline for this change, but said it would take place in the “coming weeks.”

It is unclear how Google plans to implement these policies, and how long sensitive locations will remain on users’ location timelines before the tech giant deletes them. When TTP took a phone to an abortion clinic, the clinic’s exact location remained in Google’s location history for more than two weeks, suggesting that either Google has not yet implemented these changes or the company’s system for detecting and removing sensitive locations is faulty. What is clear, however, is that users’ safety and security is threatened by Google tools that allow other people to track their locations without their consent.

Testing Google’s privacy protections post-Roe

Following the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health decision overturning Roe v. Wade, many Americans rushed to delete period-tracking apps over concerns they could be used for prosecution in states where abortion is illegal or subject to strict limitations. But as many experts have pointed out, ubiquitous technologies like Google Maps and search pose a far greater risk to privacy.

Location data may prove to be a particularly contentious issue in the coming months, given that some states are considering laws that would make it illegal for women to travel out of state for abortion procedures.

Stories and posts about how to track people using Google's tools are widely available online. To test Google’s approach to location privacy, TTP turned to one real-world example for inspiration. In a September 2021 post on the Malwarebytes blog, a researcher described how he had logged in to his account on the Google Play Store from his wife’s phone to install an app. At the time, he had his Google Maps Timeline feature enabled. After downloading the app, he forgot to log out of the Google Play Store. Shortly after, he began receiving location updates from his wife’s phone, even though her own phone’s location history was switched off.

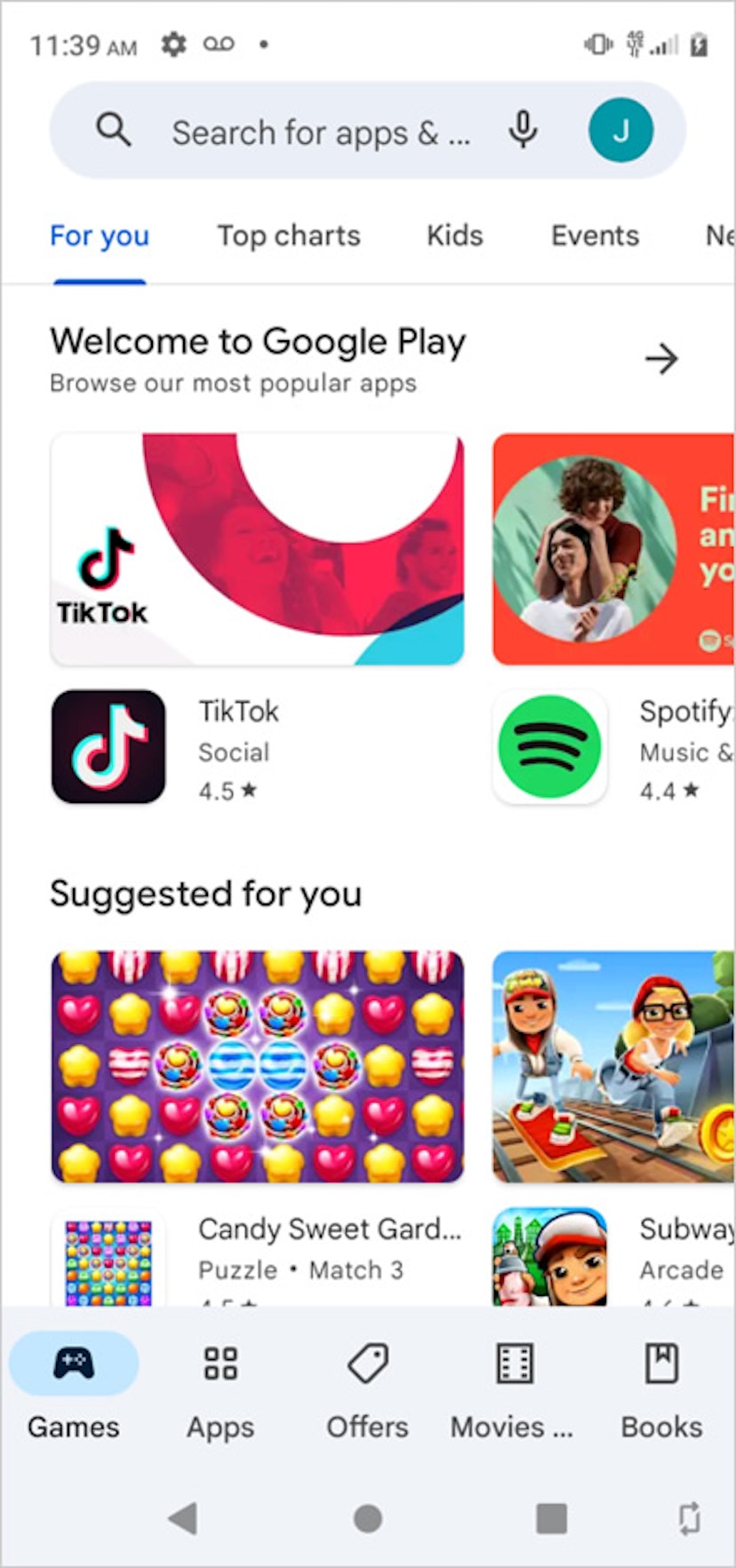

Google Play Store

The researcher said he contacted Google about this problem. TTP's experiment shows that 10 months later, Google has failed to close this dangerous loophole.

It is easy to contemplate a scenario in which a spouse, parent, or employer might log in to the Play Store on someone else’s phone. Anyone who provides technical help to someone else, buys them an app, or manages something on their device might have a reason to log in to Google Play. Someone with ill intent could easily log in to the Play Store under the guise of looking at a photo or website on another person’s phone.

Google makes it difficult to identify which account is logged in to the Play Store. The app displays a small icon with the first letter of the account holder’s name in the upper right-hand corner. This icon is easy to miss, and a particularly determined stalker could change their own account name to match their target’s first initial. Google does not appear to send users a notification when another account logs in to the Play Store on their device.

Even if a user notices that someone else is logged in, they may not understand that having another account logged in on their phone means that the account's owner can track them. They may think, quite reasonably, that having their own location history turned off protects their privacy.

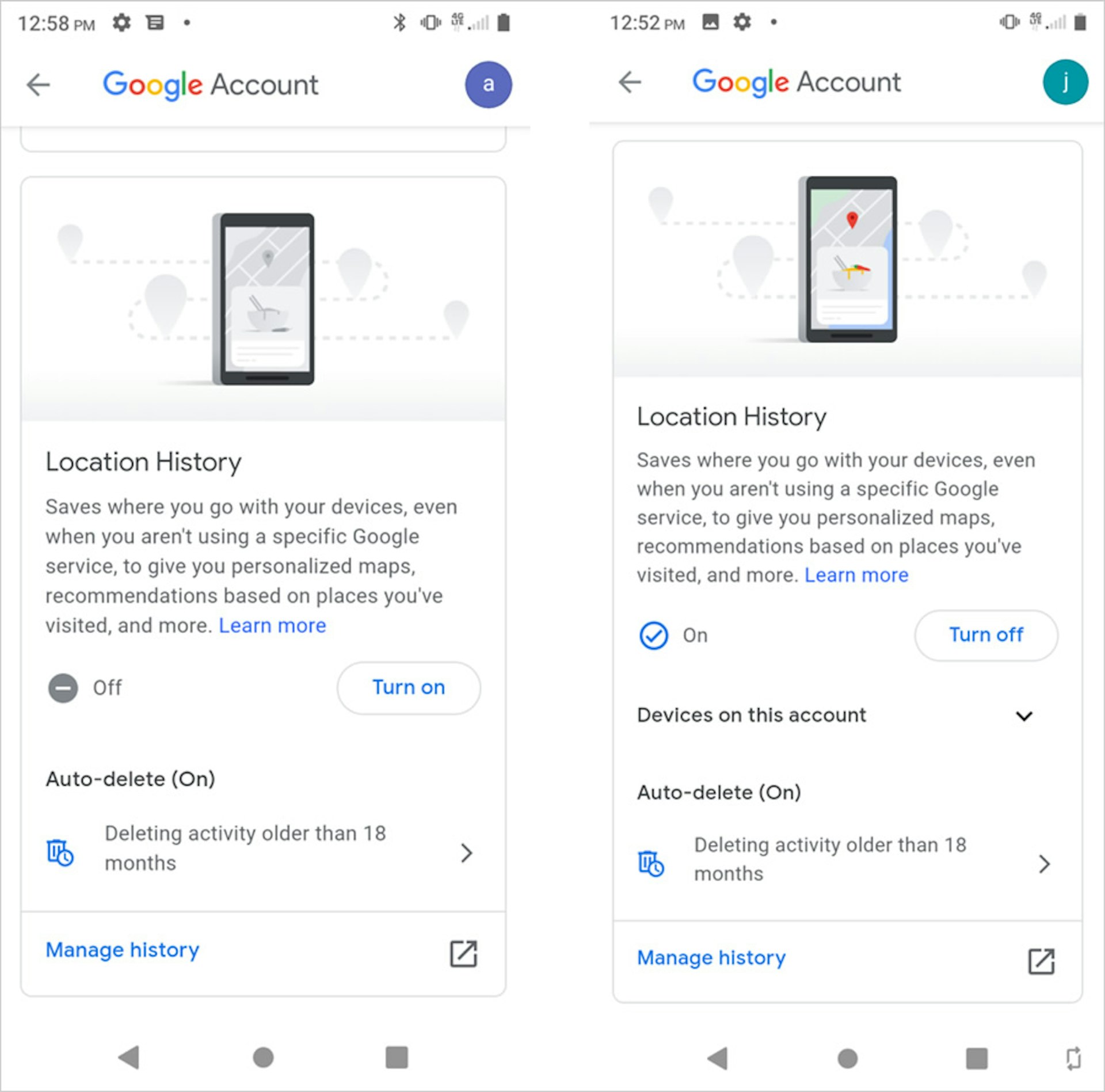

Using the Malwarebytes scenario as a model, we set up separate Google accounts on two new and previously unopened Android smartphones. One phone was designated as the “victim” and the other as the “perpetrator.” TTP turned on the location history on the perpetrator’s phone, but not on the victim’s phone. On the victim’s phone, TTP logged in to the perpetrator’s Google Play account and downloaded some apps. Over the next few weeks, TTP took the victim’s phone to several locations to see if the perpetrator was able to view its whereabouts and movements.

These were the location settings on the victim’s and perpetrator’s phone, respectively:

Google-assisted surveillance

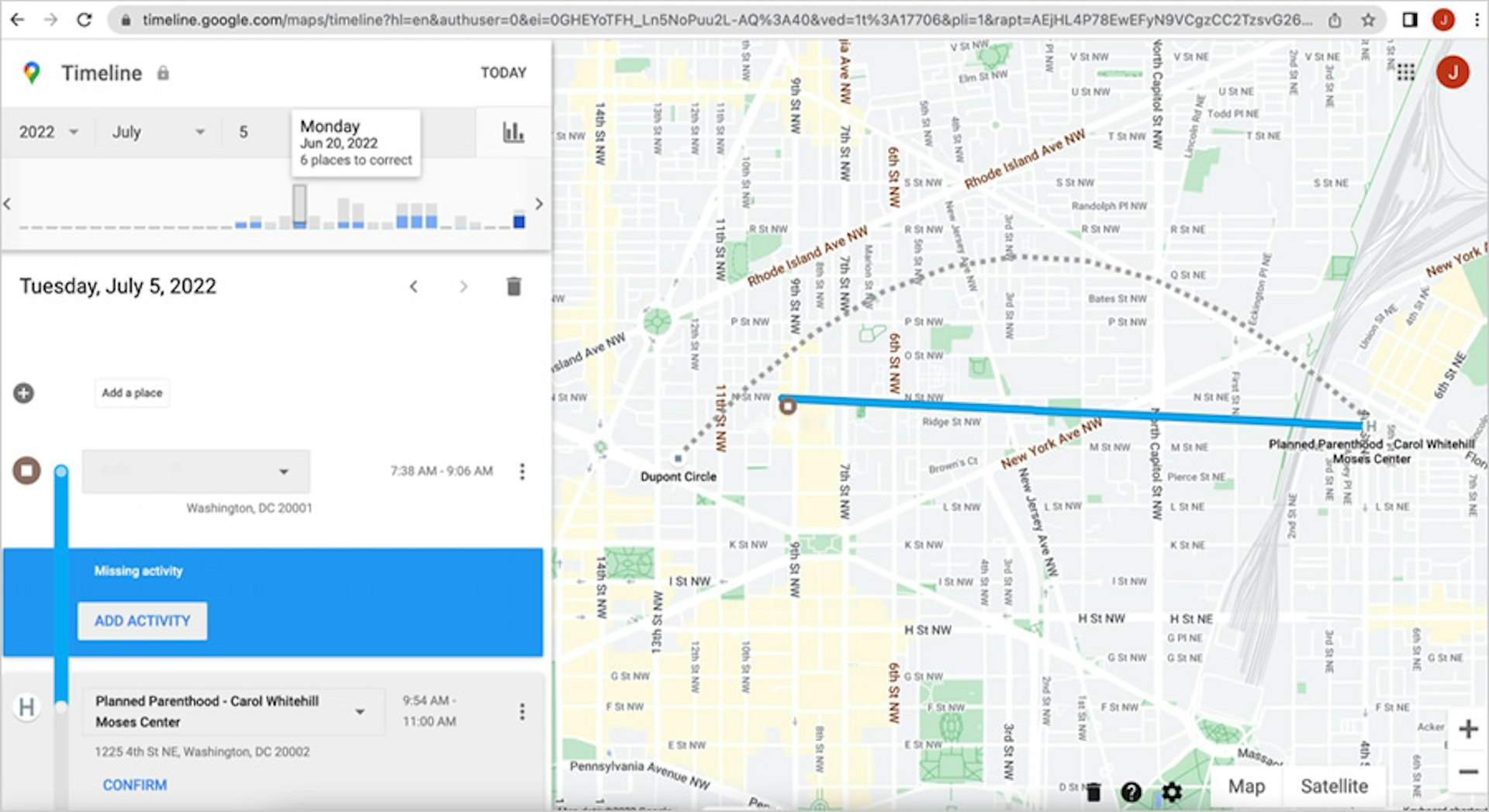

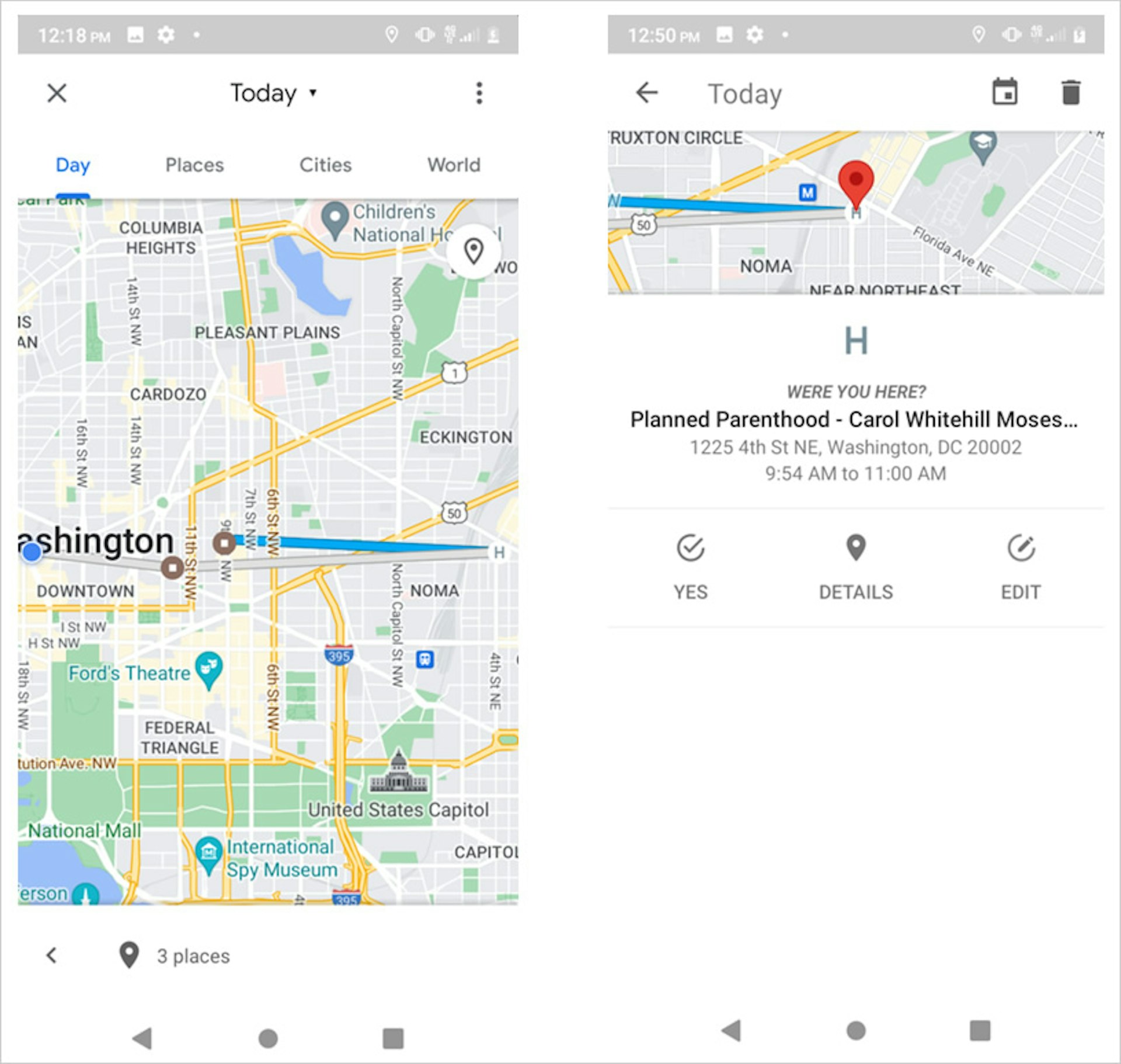

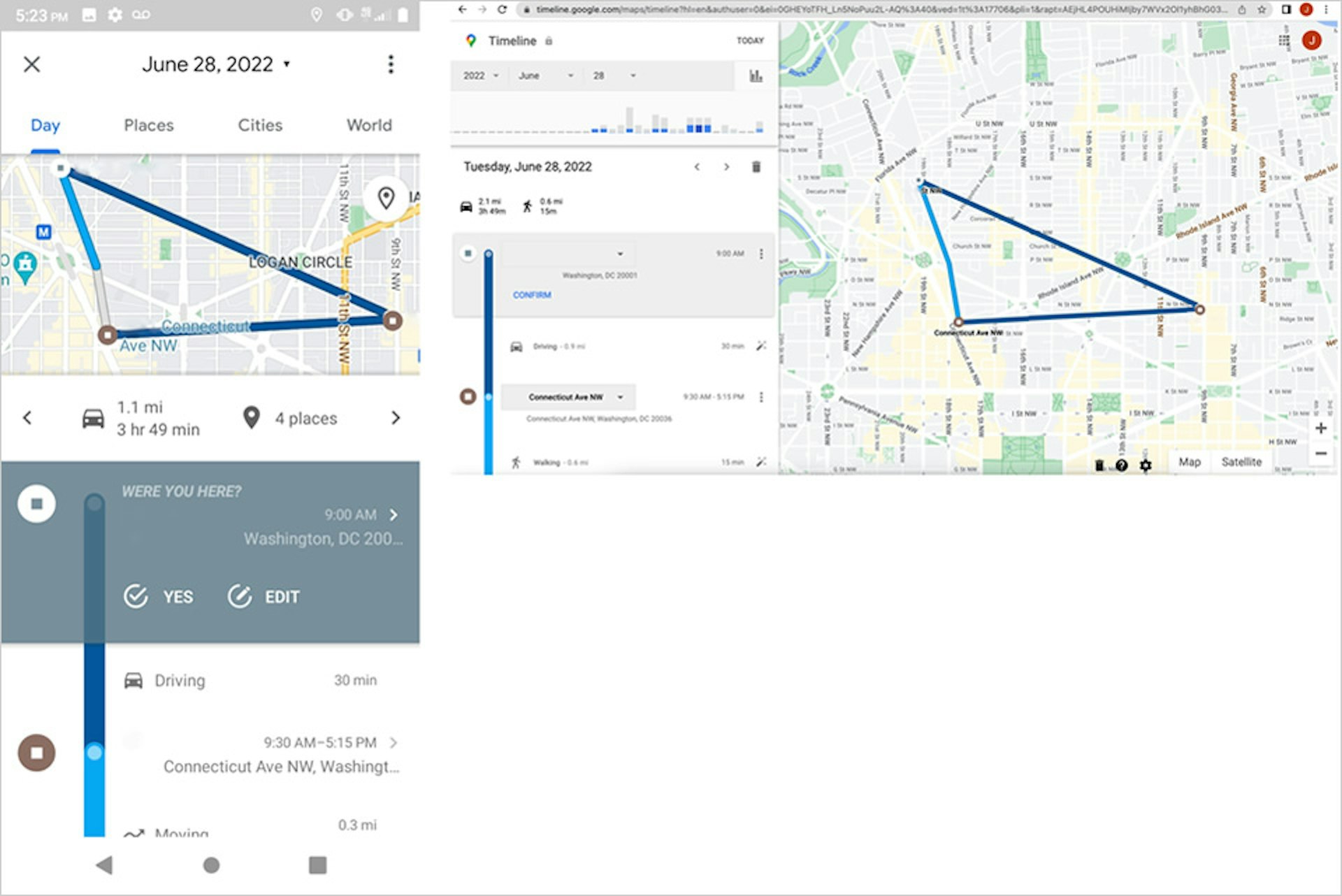

TTP found that the perpetrator was able to see the location of the victim’s phone during and after travel to a variety of locations, including a Washington, D.C., Planned Parenthood clinic that provides abortions. As seen in the screenshot below, the perpetrator could view the route and location in their own location history. (During this day, the perpetrator’s phone remained completely sedentary in a separate location.) The “J” located in the top right corner of the screenshot indicates the perpetrator’s account. Exact addresses have been removed from the screenshots to protect the privacy of researchers.

This route was also viewable via the Google Maps app on the perpetrator’s phone. Shortly after the victim’s visit to the clinic, the Timeline feature displayed the route and accurately identified the victim’s location. It even correctly noted how much time the victim had spent at the clinic. More than two weeks later, the clinic location remained in Google’s location history when viewed on the perpetrator’s phone and in a desktop browser.

TTP conducted another experiment based on a Reddit post by an individual who discovered that he could track the location of his then-girlfriend after logging in to his Gmail account on her phone. Using the same two Android phones and Google accounts, TTP logged in to the perpetrator’s Gmail on the victim’s phone, and found that the perpetrator could subsequently view the victim’s locations and routes on their own phone.

A victim might be more likely to notice if someone else is logged in to email on their phone, but they may not be aware of the consequences. A user who has their own location history turned off may believe—with good reason—that this means that Google is not storing their movements anywhere. Instead, the company’s confusing array of account settings makes it easy to inadvertently allow monitoring that could supersede intentionally chosen privacy controls. As we show in these experiments, a user who turns off location history on their phone may still inadvertently broadcast their location if another Google account with more permissive location settings later logs in to the device.

Potential for exploitation by domestic abusers

In 2019, Google cracked down on third-party surveillance apps that relay information from someone’s phone to a third party without easy detection. The company removed seven such apps after they were flagged by antivirus company Avast. As CNET noted at the time, such apps “often pose as software designed for children's safety or finding stolen phones, but they are mostly used for abusers stalking people in personal relationships.”

A year later, Google updated its policy to prohibit stalkerware apps that transmit “personal or sensitive user data from a device without adequate notice or consent” and lack “persistent notification.”

But TTP’s findings show that Google doesn’t impose these requirements on itself. At no point during our experiments did the victim’s device or account alert the user that their location was accessible to another Google account.

Google’s lack of notification is worrying, given the well-established link between domestic violence and spyware tools. As far back as 2014, NPR reported that “cyberstalking is now a standard part of domestic abuse in the U.S.” TTP found more than a dozen posts in online forums that describe people using Google apps to monitor the movements of romantic partners, exes, and crushes.

Conclusion

TTP’s experiments show that Google’s apps can be easily weaponized to track someone’s physical movements. This has troubling implications given the potential for cyberstalking of domestic violence victims. The Dobbs decision and state laws empowering citizens to inform on abortion seekers raise the stakes even higher, creating new risks to sharing a user’s location with the wrong person.

Google has pledged to remove the location histories of users after they visit places like an abortion clinic or domestic violence shelter, but our experiment found no evidence of the company doing so. More than two weeks later, our victim’s visit to an abortion clinic was still visible on the perpetrator’s phone. It remains unclear if Google will effectively implement this new policy, but even if it does, those changes will fail to protect the victims of domestic violence and stalking for whom a “sensitive” location could be home, school, or work.

Even if the company does limit the location data that it makes visible to ordinary users, it will continue to collect a host of information that could be subpoenaed by law enforcement. Google omitted all of the data it collects and stores outside of location history—search activity, nearby Wi-Fi networks, and sensor readings, for example—from its commitments to delete sensitive user information.

Google says it has users’ interests at heart, but this study shows that the company’s lust for user data—the driver behind its $257 billion advertising business—compromises users’ security and privacy.