Apple’s iconic employee uniforms are sourced from a company that was sanctioned in July 2020 by the U.S. government for its involvement in forced labor and other human rights abuses in China’s Xinjiang region, a Tech Transparency Project (TTP) investigation has found, undermining Apple’s claims to avoid suppliers that engage in such practices.

Apple Inc. has long held itself out as a crusader against forced labor, saying it has “zero tolerance” for coercive labor in its supply chain. In 2018, the company was even awarded the Thomson Reuters Foundation’s Stop Slavery Award, which recognizes companies that have taken concrete steps to prevent suppliers from using forced labor.

At a congressional hearing on July 29, CEO Tim Cook was asked about the potential for slave labor in Apple’s China supply chain. “We wouldn’t tolerate it,” Cook said. “We would terminate a relationship if it were found.”

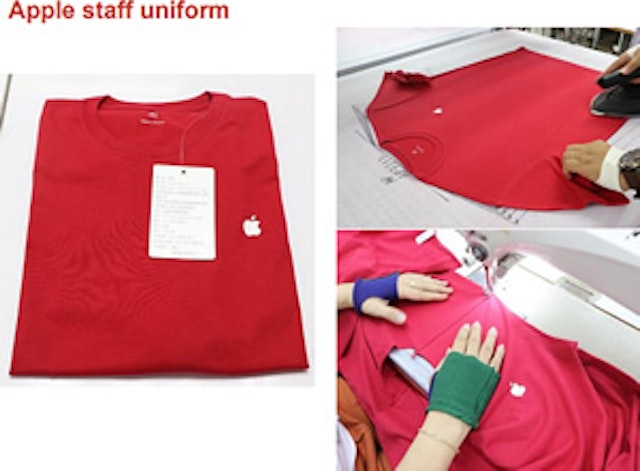

But a TTP investigation found that for years Apple has sourced T-shirts worn by its retail employees from a company tied to the use of forced labor in Xinjiang, China, where a brutal government campaign has imprisoned more than 1 million Uighurs and other Muslim minorities, transferring many directly from prison camps to factories.

Shipping records show that the supplier, Esquel Group, exports thousands of T-shirts to Apple in the United States and China. Until recently, Esquel’s website boasted of Apple being a “major customer,” according to a recent report.

Esquel, one of the world’s biggest garment makers, is based in Hong Kong and has long sourced much of its cotton from Xinjiang, a massive region in northwest China. In addition to the prison camp-to-factory pipeline, the government has pushed hundreds of thousands of impoverished minorities into involuntary labor arrangements under the guise of an economic development program, often forcing them to live and work in factories where the practice of religion is banned and workers are allowed out to see their families for only a few hours a week, if at all. Media and government reports have repeatedly tied Esquel’s farms, gins, and mills there to the use of coerced Uighur labor.

Worker in a cotton field. Sanshiliu. Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. China.

On July 20, the U.S. Commerce Department imposed sanctions on Esquel’s Xinjiang subsidiary, Changji Esquel Textile Co. Ltd., and ten other Chinese companies for their involvement in forced labor in China, finding that they had been “engaging in activities contrary to the foreign policy interests of the United States through the practice of forced labor involving members of Muslim minority groups” in the region. On July 31, the Treasury Department also announced sanctions on Esquel’s longtime partner in the region, the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC).

Apple’s reliance on such a problematic supplier—for a product as recognizable as the T-shirts worn by Apple store employees, who interact with countless customers every day—highlights the tech giant’s deep entanglement with China and the challenge it faces disengaging its supply chain from troubling labor practices.

Other Apple suppliers have also been recently linked to China’s forced labor program. In February, an Apple tech-component supplier was singled out for ties to forced labor by the Associated Press and an Australian think tank. That company, Nanchang O-Film Tech, which supplies Apple with key components of iPhone camera technologies, was also sanctioned by the Commerce Department for its ties to forced labor.

In a statement to The Guardian, which reported on TTP's findings, Apple said “Esquel is not a direct supplier to Apple but our suppliers do use cotton from their facilities in Guangzhou and Vietnam. We have confirmed no Apple supplier sources cotton from Xinjiang and there are no plans for future sourcing of cotton from the region.” The Guardian, however, added that Apple declined to say where those Guangzhou and Vietnam facilities get their raw cotton.

Esquel, for its part, has objected to its inclusion in the sanctions list, saying, "We absolutely have not, do not, and will never use forced labor anywhere in our company."

“It is imperative that leading corporations, like Apple, cut ties with companies that are implicated in forced labor in the Uyghur Region," Scott Nova, executive director of the Worker Rights Consortium, said in response to TTP's report. "This is a crucial step for ensuring that they are not complicit in the crimes against humanity that are unfolding in the region."

The Worker Rights Consortium is part of the Coalition to End Forced Labour in the Uyghur Region, which recently called on leading apparel brands and retailers to exit the region at every level of their supply chain.

Apple’s Relationship to Esquel

Apple does not publicly disclose its relationship with Esquel, so it is difficult to determine what percentage of Apple uniform T-shirts is produced by the company. Esquel referred to Apple as a “major customer” on its website before removing the reference amid recent scrutiny.

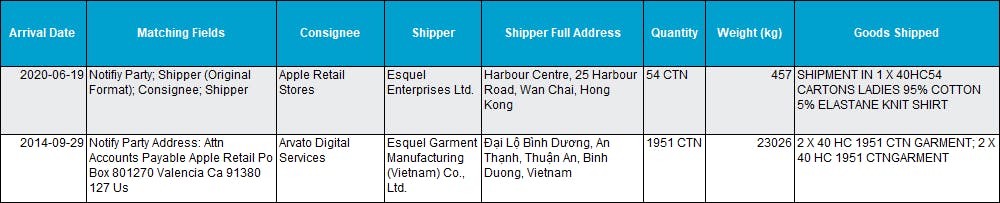

Shipping records available online show Esquel has sent thousands of garments to Apple in recent years:

- As recently as June 2020, Esquel shipped 54 cartons of knit shirts weighing 1,000 pounds to Apple Retail in Valencia, California.

- In January 2019, Esquel sent an order of 2,887 shirts from Vietnam to China valued at nearly $44,000. Apple is listed as the recipient.

- In 2014, Esquel shipped more than 1,951 cartons of garments weighing more than 50,000 pounds to Arvato Digital Services, a logistics company that works with Apple. Apple itself was listed on shipping records as the “notify party.”

TTP confirmed two of those shipments in commercial databases, which provide international shipping records to subscribers:

These shipments are likely only a sample of Apple’s dealings with Esquel, whose shipping records often do not disclose the ultimate destination of its shirts. From 2014 to 2019, Apple’s logistics company Arvato received 17 shipments from Esquel’s Vietnam operations and 16 shipments from Esquel’s Hong Kong office. It was not possible to confirm how many, if any, of these were Apple uniforms.

Outside of shipping data, there is additional evidence to support Apple’s relationship with Esquel.

In 2014, an industry journal reported that Esquel and Apple had agreed to use 10% recycled fabric waste to produce Apple uniforms.

And in September 2018, Esquel’s CEO and vice chairman John Cheh gave a presentation that highlighted the fact that Esquel produces staff uniforms for Apple.

Those uniforms appear to be made from cotton grown and milled by Esquel’s facilities in Xinjiang and assembled at one of Esquel’s three factories in Vietnam, records show. In 2014, a student in an executive MBA program described a trip to nearby Ho Chi Minh City in which he saw Apple shirts being produced in an Esquel factory.

Though the shirts are manufactured in Vietnam, Esquel’s reputation for “seed to shirt” vertical integration suggests that they almost certainly contain cotton grown and milled in Xinjiang, the source of 84% of China’s cotton. In 2010, Esquel reportedly procured all of its extra-long staple (ELS) cotton from Xinjiang—20% from its own farms and 80% from local farmers—and ginned 95% of the ELS cotton itself. In the same report, John Cheh, the CEO, said that Esquel was unique in being “truly vertically integrated.” High-quality garments tend to be produced with ELS cotton.

Esquel’s Operations in Xinjiang

Esquel Group is one of the largest producers of woven shirts in the world. It was founded in 1978 and since 1995 has been run by Marjorie Yang, the MIT- and Harvard-educated daughter of the company’s founder. The majority of its operations are in mainland China, but in response to rising labor costs, Esquel has increased automation and diversified its geographical presence to include factories around Southeast Asia.

Still, Esquel remains highly reliant on manual labor in China—most notably in Xinjiang, which produces most of the high-quality ELS cotton used by Esquel. Esquel has long been an active participant in the cultivation and processing of cotton in Xinjiang, an industry deeply tied to the use of forced labor.

According to a 2010 Harvard Business School study, Esquel’s move into Xinjiang has its roots in the 1980s, when the firm began to transform from a producer of cheap down-market goods to a contract manufacturer for well-known Western brands, including Ralph Lauren, Brooks Brothers, Nike, Patagonia and many others. These high-quality goods required ELS cotton, and Xinjiang was both the cheapest source and the one closest to Esquel’s Guangdong factories.

At the time, ELS was just 2% of Xinjiang’s cotton crop, and supply could often be unstable. To address this, Esquel began to build up its presence in the region, beginning with a spinning mill (which processes raw cotton into yarn) in the city of Turpan in 1995. It purchased another in Urumqi in 1998, and later a third, according to The Wall Street Journal. It also acquired two ginning mills (which separate cotton fibers from the seeds) in Aksu and a 6,500-acre farm in Kashgar, according to the HBS study. By 2014, the company was reportedly the largest foreign-owned enterprise in the region.

In 1998, Esquel began a twenty-year relationship with the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corp. (XPCC or “the Bingtuan”), launching Xinjiang White Field Cotton Farming Co. Ltd, a joint-venture on a 6,500-acre cotton farm that Esquel purchased in Kashgar. From its establishment until at least September 2019, it was 40% owned by Esquel and 60% by the 43rd Regiment of the Third Agricultural Division of XPCC. In 2018, the farm reportedly employed 584 people.

The partnership has made Esquel—and Apple—a party to some of worst abuses in Xinjiang.

Child Labor In The Fields

Esquel’s partner XPCC is an unusual organization. It was established in the 1950s as a paramilitary force designed to secure China’s border with Russia, to develop the region’s economy, and to bring in Han settlers to bolster Chinese sovereignty over a Turkic population more closely linked with Central Asia. The XPCC also operates as a for-profit industrial conglomerate originally designed to employ demobilized soldiers, and has a well-documented history of publicly refusing to employ Uighurs.

Today, the XPCC functions effectively as parallel government in Xinjiang, administering its own cities and running its own prisons, often focused on clearing Uighur communities off their historical land to make room for Han-dominated developments. As such, it plays an important role in China’s efforts to subdue the Uighur communities there—something the U.S. government noted in its recent move to slap sanctions on XPCC.

The U.S. cited XPCC’s connection to “serious human rights abuse against ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, which reportedly include mass arbitrary detention and severe physical abuse, among other serious abuses targeting Uyghurs.” The sanctions also target Sun Jinlong, described as a former political commissar of the XPCC, and Peng Jiarui, named as a deputy party secretary and commander of the organization.

Around the time Esquel was setting up its JV with XPCC in the 1990s, the organization was executing a crackdown on Islam, demolishing mosques and religious schools, and locking up thousands of protestors in the city of Ghulja.

From 2005 to 2011, America’s Congressional-Executive Commission on China issued a series of reports showing how the Xinjiang government forced almost a million students per year to spend weeks working 12-hour shifts picking cotton on XPCC farms. During this time, Esquel’s JV with XPCC produced 15% to 20% of Esquel’s cotton.

The Xinjiang Ministry of Education told local media that the program was intended as skills training, but simultaneously referred to a shortage of workers and allowed students’ families to pay a fee to exempt their children from the work. Children unable to meet their quotas of cotton (reportedly between 15 and 25 kilograms per day, or around 33 to 55 pounds) often brought parents or grandparents to help.

The final Commission report on the issue, in 2011, cited an incident in which the same XPCC division that partnered with Esquel in Kashgar—the Third Agricultural Division—was found to be using child labor in that city:

According to a September 24, 2011, Bingtuan News Net article profiling cotton harvesters, the 44th Regiment (3rd Agricultural Division, Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps) Number 1 Middle and Elementary School in Kashgar district organized students to “help with agriculture” by picking cotton… A blogger describing himself as a first-year junior high student (7th-grade student) at the same Kashgar school reported that his school had arranged for students to pick cotton, with daily quotas of 25 kilograms.

Uighur workers at a cotton factory in Awat county, in China’s Xinjiang region.

Aside from its use of child labor, the XPCC has been widely linked with other human-rights violations. In 2019, a Uighur activist told the U.S. Congress that the XPCC was “powered by forced labor,” referring to the organization’s practice of importing prisoners from China’s interior to work at the XPCC’s businesses in Xinjiang. Late last year, the Better Cotton Initiative, an NGO opposing the use of forced labor in cotton production and processing, stopped working with the XPCC.

At around the same time, the U.S. Department of Commerce added the XPCC’s police force to the “entities list,” which restricts the export of sensitive technology, because it was “implicated in human rights violations and abuses in the implementation of China’s campaign of repression, mass arbitrary detention, and high-technology surveillance against Uyghurs.”

In September 2019, Esquel’s 20-year lease agreement with the XPCC expired just as global outrage over China’s crackdown in Xinjiang was reaching new levels. Citing the XPCC’s “change of policy direction,” Esquel announced it would end the partnership and divest its shares, a process that was completed on April 20, 2020.

It is unclear whether Esquel continues to buy cotton from XPCC today, but the company still operates three spinning mills and two cotton ginning mills in Xinjiang.

Apple’s Growing Exposure in China

The sanctioning of two of Apple’s suppliers underscores the tech giant’s dependence on China, both as its second-largest retail market and the key link in its supply chain, which has been beset with problems ranging from tariffs to coronavirus disruptions and now human rights violations.

Much of that supply chain was built by Apple CEO Tim Cook, who was hired in 1998 to re-think Apple’s operations. He quickly shut down many of Apple’s manufacturing centers and moved them to the PRC, where the work was done by contract manufacturers and suppliers.

It’s unclear whether Cook was personally involved in approving Esquel or O-Film as Apple suppliers, but it will be up to him to handle the delicate response to their ties to forced labor, an issue Apple has been outspoken about opposing.

The company made forced labor a core violation of its Supplier Code of Conduct in 2008. In 2015, Apple went further and began interviewing supplier employees. In 2018 Apple was awarded the “Stop Slavery Award” by the Thomson Reuters Foundation for “leading the industry in eradicating forced labor.”

But Apple has been reluctant to comment on its ties to China’s forced Uighur labor despite detailed allegations in reports from The Wall Street Journal, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, and The New York Times.

Esquel was publicly linked to the Xinjiang labor-transfer program in May 2019, when The Wall Street Journal published an article naming it as one of several Chinese companies that “have become entangled in China’s campaign to forcibly assimilate its Muslim population.”

The article quoted Esquel CEO John Cheh saying that in 2017 government officials began offering the company Uighurs from southern Xinjiang as workers. Esquel took 34 in total, Mr. Cheh said, but insisted, “We were in no way forced to employ anyone.”

The article did not mention Apple.

Apple has made the fight against forced labor a core part of its supply chain responsibility program.

On February 29, 2020, both Apple and Esquel were named in a report by the Australian Strategic Policy Initiative (“ASPI”), a think tank that has received money from the U.S. State Department and other countries to conduct research on Xinjiang. The report, “Uyghurs for Sale,” described the practice of shipping Uighur labor, often under coercive conditions, out of Xinjiang to work in factories in China’s prosperous eastern provinces. The report contained a section on Apple that detailed its supplier O-Film’s use of such labor.

The report separately highlighted a transfer of Uighur laborers to an Esquel company as part of a government “job fair,” described in a post on a Communist Party website in October 2019. The post strongly suggests that the fair is part of the coercive labor-transfer program, the TTP found. It states that, following the fair, 46 workers were transferred within Xinjiang and 13 outside Xinjiang. Mongolküre County has been arranging such labor transfers since at least 2016, and claims to have increased its volume of transfers in 2019 in part of its poverty-alleviation initiatives.

Following ASPI’s report, members of Congress have pushed for the passage of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, which calls for a variety of sanctions on people and companies involved in forced labor in Xinjiang. The Act instructs the president to compile a list of sanctioned entities, and specifically asks him to investigate six particular companies, including both Esquel and Litai. Representative Ilhan Omar also sent letters to Tim Cook and the CEOs of other large companies mentioned in the ASPI report demanding information about their links to forced labor.

Some of Esquel’s customers—including two mentioned in the WSJ’s May 2019 report—also began to distance themselves from the company.

Nike, which in 2015 had honored Esquel with the Nike Materials Sustainability Index Award, said it would investigate the allegations. Patagonia, which sources from Esquel’s Vietnam factories, announced in July 2020 that it would eliminate Xinjiang entirely from its supply chain.

Apple’s silence on the human rights crisis in Xinjiang—and its ongoing sourcing from companies that participate in that repression—speak volumes about Apple’s entanglement with China, where forced labor is not the product of a rogue factory but a government program aimed at coercing Muslim minorities to comply with Communist Party doctrine.

Note: This report has been updated to include a statement Apple gave to The Guardian about TTP's findings. It was also updated to correct the year a Uighur activist gave testimony to Congress. That testimony was in 2019.