A Tech Transparency Project investigation has found that Apple’s role in China’s censorship regime goes further than was previously known.

Apple acknowledges taking down hundreds of apps from its App Store at China’s request, but says the majority of those removals were related to porn and gambling, which China considers illegal.

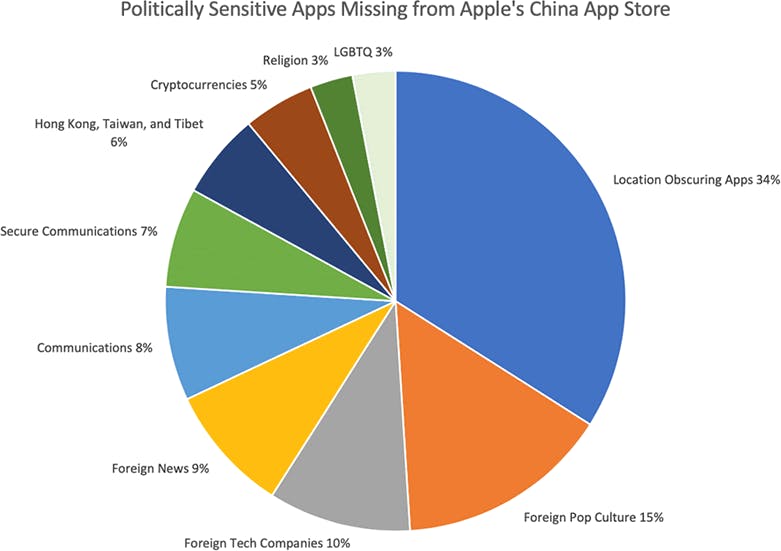

A TTP analysis found a starkly different picture: Of 3,200 apps missing from the China App Store, almost a third relate to hot button human rights topics targeted by China’s censors, such as privacy tools, Tibetan Buddhism, Hong Kong protests and LGBTQ issues. Porn and gambling apps made up less than 5 percent.

TTP also found significantly more missing apps than those taken down at China’s request—suggesting Apple is proactively blocking sensitive apps to protect its relationship with China.

A recent report in The Information said that Apple “screens out apps that refer to sensitive topics” in its China App Store, something the company has not publicly acknowledged. The New York Times reported in December that Apple executives censor Apple TV projects that may offend China. Apple Senior Vice President Eddy Cue reportedly said, “the two things we will never do are hard-core nudity and China. Prior to that, Cue had also told Apple TV partners to “avoid portraying China in a poor light,” according to Buzzfeed News.

Apple’s censorship of the China App Store raises questions about the company’s commitment to free speech and human rights—and the completeness of its transparency reports, which offer aggregate numbers but no detail.

In September, Apple released a human rights policy that stressed the company’s commitment “to an open society in which information flows freely.” The policy made no mention of China, but came after a shareholder rebellion in which more than 40 percent of Apple shareholders demanded the company release details of China’s efforts to limit free speech on Apple products.

The policy, which tacitly acknowledges that Apple honors national laws over human rights when they conflict, is unlikely to appease its critics. The NGO SumOfUs, which organized the shareholder action, says Apple’s new policy does not go far enough, and has filed another shareholder resolution demanding the company disclose how it squares the policy with its actions in China.

Human rights groups say Apple’s censorship most hurts the targets of China’s authoritarian policies.

''By using self-censorship to not offend China and risk losing the Chinese market, Apple fails to consider that the lives of millions of Uyghurs, Tibetans, Hong Kongers and others are at risk,” said Zumretay Arkin, the Program & Advocacy Manager at the World Uyghur Congress. “Apple's response to human rights groups advocating against Apple Censorship was that they're simply complying with local laws. But the fact is that they have actively chosen to comply with a regime that is committing genocide, and the worst human rights violations. Apple needs to respect its own set of values and act accordingly.''

Apple has long been criticized for censoring specific apps on behalf of China. As young Hong Kongers fought for their independence, Apple removed, at Beijing’s request, a popular app for protests, HKMap.live. A similar pro-democracy app, PopVote, recently disappeared for reasons that remain unclear. Apple has removed podcast apps for content that included support for Black Lives Matter and removed the Taiwanese flag emoji for users in mainland China, Hong Kong and Macau.

But the scope of the problem is difficult to measure. TTP’s analysis used data collected by Great Fire, an advocacy group that monitors censorship in China, to identify and categorize apps that exist on Apple’s App Stores in other countries but are missing in China. The fact that an app is not available in China is not a sure sign of censorship—some app developers choose not to offer apps there or have a Chinese language equivalent. But given Apple’s total control over the App Store and the sensitive topics covered by missing apps, many are likely the result of Apple censoring on behalf of Beijing.

The TTP review identified 3,257 apps missing from the China App Store. Of those, 964 relate to politically sensitive topics such as:

- Hundreds of proxy and VPN apps that Chinese citizens could use to evade the country’s censors.

- Several apps used by Hong Kong pro-democracy protestors to communicate and organize.

- More than two dozen applications made for the LGBTQ community, including dating applications and chat forums.

- Over 100 missing foreign news publications, spanning publications in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Tibet, Europe, and the United States.

- More than a dozen apps involving the teachings of the Dalai Lama.

- Other apps about Christianity, Falun Gong, or Islam.

Apple often justifies its removal of applications from foreign App Stores as “complying with local laws.” Under China’s authoritarian rules, gambling and crypto-exchange apps are illegal, while games and VPNs often require a special government license. But many of the politically sensitive apps unavailable in the China App Store—such as those about religion and LGBTQ issues—do not appear to be explicitly illegal.

Apple’s role in China’s censorship regime has stoked concerns about its monopoly over the App Store, which is currently the subject of antitrust investigations in the U.S., EU, and beyond. It also raises broader questions about the company’s ties to China. While tech giants like Facebook and Google were kicked out of China for failing to comply with its authoritarian rules, Apple has embraced China as its third largest market by revenue and relies on China for much of its supply chain.

As TTP reported in August, Apple’s supply chain—both electronics and its employee uniforms—rely upon the labor of China’s Uighur minorities, who are forced to work in factories as part of a harsh crackdown by the Chinese government that some consider genocide.

Apple’s embrace of China increasingly puts the company in conflict with human rights, free speech, and United States government policy. Citing national security concerns, in August the Trump administration moved to block all transactions with the parent companies of WeChat and TikTok, a move that would hurt Apple’s bottom line.

Ironically, Apple is vigorously objecting to U.S. efforts to ban the Chinese apps—something the company routinely does for China.

Apple’s App Removal Disclosures

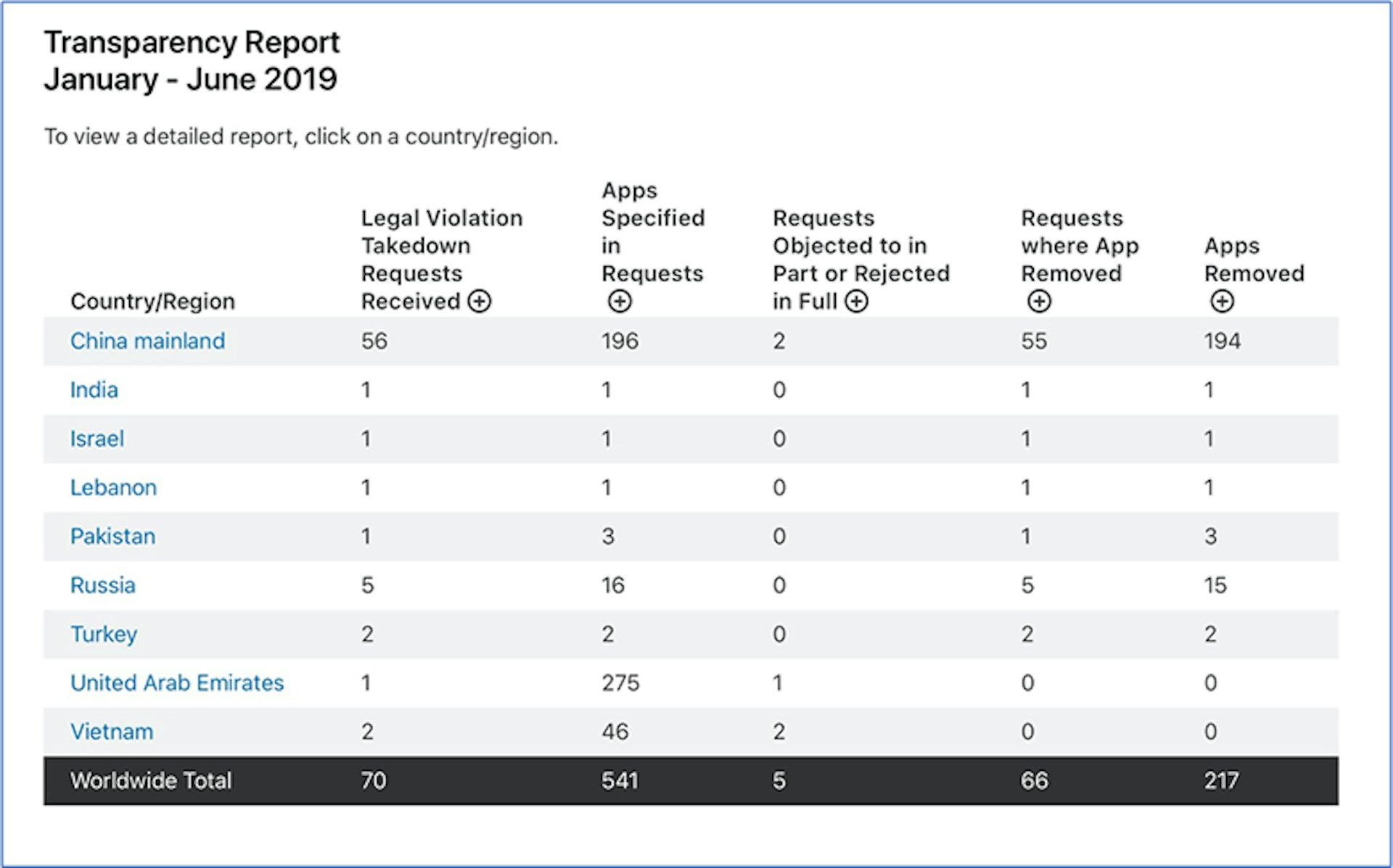

TTP’s investigation raises questions about the accuracy of Apple’s bi-annual transparency reports, where the company discloses data and takedown requests from various countries, including China.

From July 2018 to June 2019, Apple disclosed that it had removed 805 applications at the request of the Chinese government. The “majority” taken down for legal violations involved “pornography and illegal content,” while the “vast majority” of those removed for a platform violation involved illegal gambling. In early July 2020, Apple also removed more than 2,500 mobile games from China’s App Store for not having an official license from the country’s regulators.

It is rare for countries other than China to request mass removals of applications by Apple. The United States did not request for any apps to be removed from July 2018 to June 2019. Of the 96 countries included in Apple transparency reports, 10 other governments requested app removals from July 2018 to June 2019—none to the extent of China. The next closest country was United Arab Emirates with 275 requests and one removal.

But Apple’s public disclosures appear to omit thousands of apps that are missing from the company’s China App Store, suggesting Apple may have taken them down proactively rather than in response to a demand by China.

To investigate the scope of Apple’s censorship on its China App Store, we analyzed data collected by Great Fire, an activist group that works to hold the Chinese government accountable for internet censorship. Great Fire compiled the data as a part of its Apple Censorship project, which has tracked the availability of applications across App Stores worldwide since its launch in February 2019.

Great Fire searches for specific applications on Apple’s App Stores around the world and publishes data on which countries are missing which apps. Great Fire’s data is broad but not comprehensive, as it only includes apps users search for.

TTP obtained raw data from Great Fire’s website and examined each of the apps to confirm Great Fire’s research and gain more insight into the function of the apps. We then assigned each application to one of 13 categories based on the app description. The categories were: porn and gambling; religion; Hong Kong, Tibet, and Taiwan; location obscuring applications; cryptocurrencies; secure communications; foreign technology companies; foreign news; communications; foreign culture; LGBTQ; games; and other.

Apple doesn’t disclose apps it voluntarily blocks from its China App Store, so it is difficult to know why specific apps are missing and how many of them are covered by Apple’s transparency report. In some cases, app developers have opted not to work in China. But for nearly 1,000 reviewed by TTP, the apps touch on politically sensitive topics that China routinely censors, suggesting Apple may be pro-actively blocking them.

Location Obscuring Apps

The TTP review found 330 apps like VPNs, which allow users to obscure their location, were missing from Apple’s China App Store, making up 34% of politically sensitive apps reviewed.

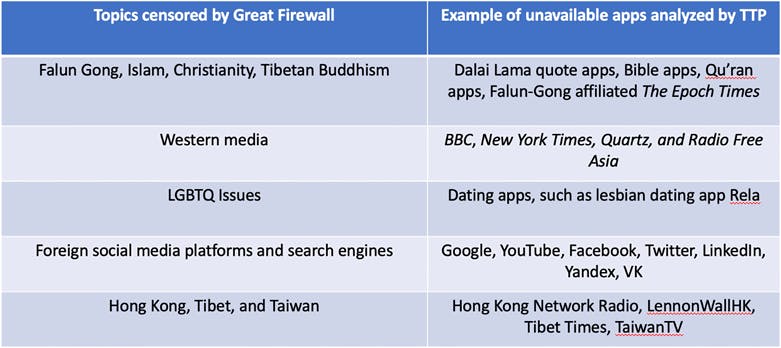

VPN’s are a key tool for Chinese citizens to evade China’s tight control over the information available to its citizens under the “Great Firewall”—a set of laws and regulations that block Chinese citizens’ access to foreign websites and internet tools. The blocked content covers areas including foreign tech platforms, such as Google and Facebook; foreign news publications, like The New York Times and the BBC; and content on religious groups, such as Tibetan Buddhism and Falun Gong.

The Great Firewall restrictions increased in the 2000s; however, Chinese people most commonly turn to VPNs to circumvent these restrictions and gain access to the online world. To combat this, the Chinese government seemed to have enlisted Apple’s help in blocking Chinese citizens’ access to VPNs in 2017, resulting in the technology company taking down VPN apps en masse from the China App Store.

Apple’s decision to removes VPNs from China’s App Store may comply with Chinese law, which requires VPNs to register with the government, but severely limits the free speech of Apple’s Chinese customers—in stark contrast with Apple’s professed values.

Apple CEO Tim Cook speaks at the 2017 Free Expression Awards ceremony at the Newseum in Washington, D.C. Credit: C-SPAN.

“This is a responsibility that Apple takes very seriously” Cook said in a 2017 speech accepting the Newseum’s Free Expression Award for defending the First Amendment. “First we defend, we work to defend these freedoms by enabling people around the world to speak up. And second, we do it by speaking up ourselves.”

The discrepancy between what Apple preaches and how it acts has not gone unnoticed by VPN developers. For example, VyperVPN executive Sunday Yokubaitis wrote in a 2017 blog post, “If Apple views accessibility as a human right, we would hope Apple will likewise recognize Internet access as a human right (the UN has even ruled it as such!) and would choose human rights over profits.”

In a follow-up blog post titled, “Mr. Cook, Where is the Censorship Red Line for Apple?”, Yokubaitis asked, “What precedent does this set for Apple in other countries with repressive regimes?[…] Will Apple become the Minister of Information for these repressive regimes?”

Members of Congress also took notice of Apple’s contradictory behavior. A bipartisan pair of senators, Ted Cruz (R-Texas) and Patrick Leahy (D-Vermont), asked Apple to explain its decision to restrict VPNs in China referencing how Cook’s award of the Free Expression Award directly contradicts his company’s policies. The letter continues:

While Apple’s many contributions to the global exchange of information are admirable, removing VPN apps that allow individuals in China to evade the Great Firewall and access the internet privately does not enable people in China to “speak up.” To the contrary, if Apple complies with such demands from the Chinese government it inhibits free expression for users across China, particularly in light of the Cyberspace Administration of China’s new regulations targeting online anonymity.

In response, Apple’s then-lobbyist Cynthia Hogan, now an top advisor to President-elect Joe Biden, wrote that Apple disagrees with China’s decision to ban VPNs but that the company believes it can best promote “fundamental rights” by keeping a presence in the country.

Hogan quoted Cook as saying: “We believe in engaging with governments even when we disagree.”

Games

The TTP investigation found 785 of the unavailable applications were labeled as mobile games by Apple. It is likely that many of them are unavailable in the China App Store due to not having a license from China.

In the summer of 2020, Apple reportedly removed thousands more mobile games from the China App Store for not having an official license from the country’s regulators. China’s gaming regulator claimed this licensing was required to crack down on youth gaming addiction, to regulate content in the games, and to limit the number of games on the market. Prior to July 2020, gaming apps could be on China’s iOS store while their license applications were under review.

There may also be financial and political motives. China is one of the world’s largest markets for online games, with a greater than $30 billion domestic market that appears to be growing. Licensing game apps allows China to protect its domestic gaming industry, led by developers like ByteDance, while monitoring the conversations young people have on those apps. China reportedly approves about 1,500 yearly, of which roughly 300 go to foreign games.

Prior to this mass removal, Apple removed a game that simulates a global pandemic called Plague Inc. from the China App Store in February 2020—the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. After being in the most played games in China and on the App Store for years, Plague Inc. developers said they were informed that the game “includes content that is illegal in China as determined by the Cyberspace Administration of China.” The developers added in a press release that they were unaware of any illegal content, or if the coronavirus pandemic in China played a role.

Foreign Popular Culture Apps

TTP found 140 applications that relate to foreign art or culture missing from Apple’s China App Store. This includes apps relating to movies, TV shows, and music as well as sports, travel guides, and language learning applications.

Some of the unavailable applications include popular video streaming services, such as Netflix and HBO GO, whose content is not licensed to air in China. Others, like the NBA, have China-specific apps in the App Store. Spotify formed a strategic partnership with similar companies in the region, like Tencent Music, rather than host its own app in China.

But some of these missing apps may be the result of censorship. For example, Apple removed podcasting app Pocket Casts from the China App Store at the request of China’s Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC). Surprised and confused by the move, Pocket Cast developers contacted Apple for clarification and the tech company directed the app developer to contact CAC directly.

In a Twitter thread on the matter, Pocket Casts called the move “quite alarming.” The company said it was unsure why they were removed from China but assumed it was due to certain content available on the app that the Chinese government objected to.

“We assumed that what they’d want us to remove are specific podcasts, and possible [sic] some of the Black Lives Matter content we’d posted,” a Pocket Casts spokesperson told TechCrunch.

Foreign News Apps

In total, TTP found 89 applications that relate to foreign news publications missing from the China App Store, spanning publications such as the BBC, The New York Times, and The Times of India. (This does not include applications relating to Hong Kong, Taiwan, or Tibetan media which will be covered in a later section.)

U.S. publications make up 61% of the unavailable news applications TTP examined. In some cases, the apps are local news outlets for American cities, but the majority are national and international publications.

Apple has a history of banning media apps that feature unfavorable coverage of the Chinese government. In December 2016, Apple removed The New York Times at the request of Chinese authorities without appearing to specify the specific local laws the paper violated. Similarly, Apple removed the Quartz media app in October 2019, allegedly due to the publication’s coverage of the Hong Kong protests. Other American news outlets unavailable in China are MSNBC, CBS News, and BuzzFeed News.

Hong Kong, Tibet, and Taiwan

TTP found that 61 of the unavailable applications related to the contested Chinese territories of Hong Kong, Tibet, and Taiwan.

Hong Kong

There are 35 applications relating to Hong Kong that are unavailable on China’s App Store. Of the 35 apps, 16 are news publications, four are specific to the Hong Kong independence efforts, six are Hong Kong-specific communication platforms, and the remaining nine are miscellaneous Hong Kong-specific apps for entertainment applications, shopping, etc. (One of the applications, MZ+快訊, is a news publication catering to both Hong Kong and Taiwan, and therefore, is counted in both sections.)

Apple has taken down or blocked several apps relating to Hong Kong protests from China’s App Store. One prominent instance is the case of HKMap.live. Launched in fall 2019, the HKMap.live app crowdsources the location of protesters and police. In a statement the South China Morning Post, Apple said it took the app down because it “has been used in ways that endanger law enforcement and residents in Hong Kong.”

HKmap released a backup version of the app called BackupHK: HKmap.live即時地圖 after the original was taken down. Currently, BackupHK is no longer available in China, Hong Kong, or the U.S.

According to Great Fire data, a second app called LennonWallHK has been unavailable on the China App Store since September 2019. LennonWallHK is a crowdsourcing app to build “Lennon Walls” throughout the city. The political art pieces are inspired by the original John Lennon Wall in Prague and became popularized during the 2014 Hong Kong democracy protests. Protestors post thousands of sticky notes in public places spreading pro-democracy messages. LennonWallHK is still available in Hong Kong and the United States.

In July 2020, Apple reportedly did not allow the app PopVote, which Hong Kong’s opposition used to hold unofficial elections in the territory, on its platform. Google Play, on the other hand, did.

Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism

The TTP investigation found 25 Tibetan apps unavailable on the App Store, including 13 apps relating to Buddhism or Tibetan Buddhism, nine Tibetan news outlets, and three devoted to Tibetan culture, language, or tourism.

China has long had a conflicted relationship with Tibet. In 1959, Tibet was officially incorporated into the People’s Republic of China as an autonomous region, but the Chinese government believes it has had sovereignty over Tibet since the late 13th century. When China took over Tibet in 1959, it began suppressing aspects of Tibetan Buddhism and declared the Communist Party would appoint the foremost spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism, the Dalai Lama. As a result, the current Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, fled the country fearing for his life and has since resided in India.

As a result of this, practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism in China have been persecuted for years. That policy appears to extend to Apple’s China App Store, where the majority of unavailable Tibetan Buddhism apps TTP analyzed related to the teachings or quotes from the Dalai Lama.

Taiwan

TTP found 16 applications relating to Taiwan missing from the China App Store, 10 of which are news applications and four of which relate to Taiwanese restaurants or geography. (One of the applications, MZ+快訊, is a news publication catering to both Hong Kong and Taiwan, and therefore, is counted in both sections.)

As with Tibet and Hong Kong, Taiwan has a contentious relationship with China. China claims Taiwan is a territory of the country, but Taiwan considers itself a sovereign nation with its own government.

The majority of unavailable applications TTP analyzed related to Taiwanese news publications, such as TaiwanTV and United Daily News.

Religion

Along with the unavailable Tibetan Buddhism apps, TTP found 18 other missing apps that relate to religion—five to Christianity, nine to Falun Gong, and four to Islam.

Religious persecution in China has ebbed and flowed over the years; however, recently President Xi Jinping has made it a priority to control religious belief in China.

During an April 2016 keynote speech at the Communist Party National Conference on Religions, Xi Jinping announced a grand plan to harness religion as a tool for indoctrinating the Chinese socialist ideology while also guarding against “overseas infiltrations.”

Falun Gong

Falun Gong is a religious practice that started in China in the 1992. Falun Gong quickly gained popularity, with an estimated 70 million practitioners by 1999. Falun Gong’s independence and widespread popularity led the Chinese government to embark upon a campaign to eradicate it by blocking websites that mention the practice.

All of the seven Falun Gong-related apps are news publications, including the well-known Epoch Times, a U.S.-based paper founded by Falun Gong members that has become a prominent force in conservative media and known for anti-China rhetoric.

Islam

TTP identified four unavailable applications relating to Islam.

Three of the four are Quran quote applications and the last is a financial forum for the “Islamic Finance Community.”

China has a history of weaponizing mobile apps to surveil and oppress the local Uighur ethnic minority, according to a recent report of leaked government documents. The documents revealed that Chinese authorities were tracking the Muslims through an app called Zapya, which allows users to share religious Islam teachings and download the Quran.

Zapya is still available in Apple’s China App Store and has never been removed, unlike many other religious apps. The leaked documents did not explain how the government obtained Zapya user data, or if Apple was actively cooperating with Chinese authorities. However, China has used its unprecedented access to Apple user data to monitor Uighur Muslims in 2017 through the vulnerabilities in Apple’s iOS system.

Dozens of apps that mention “Allah” or “Islam” were still available on the China App Store, whereas apps about Tibetan Buddhism or Falun Gong were not.

Christianity

TTP found five applications relating to Christianity were not available in China.

The persecution of Christians in China stems from the Party’s fears over the religion’s strong ties to the West. As a result, the CCP treats Christianity as a national security threat and, over the years, has destroyed churches, detained pastors, and censored the Bible and church decorations.

There is a state-sanctioned sect of Christianity called the Three-Self Church which is overseen by the United Front Work Department of the Communist Party of China. Numerous watchdog groups have reported on the Chinese government threatening churches to convert to the Three-Self Church doctrine or have their congregation broken up.

One of the unavailable applications is the official app for The Church of Almighty God, an outlawed Chinese Christian religious organization that state media dubbed the nation's “most dangerous cult.” Similar to Falun Gong’s beginnings, The Church of Almighty God began in China in 1991, reportedly amassed millions of Chinese followers, and was outlawed by 1995, resulting in a mass exodus of its followers from China.

Foreign Technology Companies

TTP found 93 unavailable apps relating to technology companies outside of China.

Most of the apps relate to major technology companies like Facebook, Google, Instagram, LinkedIn and Twitter that have been banned in China.

China’s blocking of Facebook and Twitter has its roots in a crackdown on minority communities such as the Uighurs. In July 2009, the capital of the Uighur-majority Xinjiang had a series of riots over the repression of Uighurs by the Chinese state. When the protestors organized using Facebook and Twitter, China banned the applications.

Beyond major U.S. social media applications, missing applications also include Russia’s social media platform VK, Apple’s COVID screening app, and TikTok. Though technically not a “foreign” app as it is based in Beijing, Bytedance developed TikTok for markets outside of China while building Chinese equivalent Douyin for domestic audiences. In July 2020, U.S. politicians started investigating TikTok as a potential tool for spying and is considering banning the app all together.

LGBTQ

TTP found that 26 missing applications were made for or targeting the LGBTQ community, including chiefly dating applications and chat forums.

Though homosexuality has been legal in China for the past two decades, it is still highly stigmatized in Chinese society and censored by the government in Chinese media. Dating apps have widely been considered a critical resource for LGBTQ Chinese citizens to not only find partners, but also come out to their families.

In the past, the Chinese government has been accused of censoring dating apps on both the Google Play and Apple store, such as in 2017, when LGBTQ dating apps Rela and Zank were removed from both platforms with no explanation. The crackdown closely coincided with the legalization of same-sex marriage in Taiwan. Rela was reinstated to Chinese app stores a year later.

If Apple is in fact removing gay dating apps at the behest of China, it would be in stark contradiction to the company’s values. Apple’s CEO Tim Cook is a gay man and a vocal advocate for LGBTQ rights internally in Apple and globally.

That being said, LGBTQ dating platforms do not appear to be as widely banned on the China App Store as VPNs, and there are various gay dating apps available to Chinese users. It is unclear why some appear while others are missing.

Cryptocurrency

There are 48 missing applications relating to cryptocurrencies, including wallets, exchanges, and market trackers.

Blockchain technology has increasingly become a topic of importance to the Chinese government, which announced in 2019 it would be releasing its own digital currency. China is also funding millions of dollars of blockchain projects and education campaigns.

But the government objects to the decentralized aspects of blockchain technology and is working to systematically stamp out any versions of the technology it cannot control, such as independent cryptocurrencies.

China banned all domestic cryptocurrency exchanges in 2017, resulting in a mass exodus of Chinese blockchain companies and the ban of cryptocurrency exchanges in general. Apple subsequently appears to have removed 43 cryptocurrency exchanges from the App Store.

The ban on domestic exchanges shocked the global crypto-community as the world’s largest exchanges were from China, namely Binance, OkCoin, and Huobi. None of these exchanges’ apps are available in the China App Store today despite Beijing’s renewed interest in the technology.

Communication Apps

TTP found 76 general communication apps and 63 secure communication apps missing from the China App Store. Communication apps include video chat apps, forums, and dating, while secure communications apps use encryption for messengers and browsers.

Several of the unavailable applications are Tor browsers, which are a popular means for people around the world to securely and privately surf the internet and the dark web. Other unavailable apps include encrypted video chat platform Jitsi Meet, encrypted online messaging platform Voxer, and popular online encrypted chatroom Discord

Encrypted applications and browsers ensure that users can privately communicate with one another without fear of others online intercepting their messages or spying on their activity. Like other unavailable apps in the China iOS store, encrypted messengers and browsers are not technically illegal in China, but over the years, they’ve become increasingly blocked or censored by the government.

Appendix: Apps Missing from Apple’s China App Store

TTP used data from the anti-censorship organization GreatFire.org to identify 3,257 apps missing from the Apple’s China App Store but widely available elsewhere for Apple users.

Of those missing apps, TTP found 964 relate to the politically sensitive topics of religion, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Tibet, secure communications, cryptocurrencies, VPNs, social media platforms, and foreign media. Just 5%, or 154, related to illegal porn or gambling—the topics Apple says make up the majority of China’s takedown requests.

The politically sensitive apps missing from the China App Store touch on topics often targeted by China’s censors:

- 34%, or 330, are location obscuring applications, such as proxies and VPNs—tools widely used by Chinese citizens to evade censors.

- 15%, or 146 apps, pertain to foreign entertainment and media, including popular video streaming services such as Netflix and HBO GO; podcast and music platforms like Spotify; and sports organizations like the NBA.

- 10%, or 93 apps, are foreign tech platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Google, and Russia’s VK social media app.

- 9%, or 89 apps, are news or media outlets spanning print, video, and audios applications not based in China.

- 8%, or 76 apps, are applications users use to communicate with each other, including forums, chatrooms, messengers, livestreams, and video chats.

- 7%, or 64 apps, are secure communications which TTP defines as privacy-preserving applications that allow users to avoid surveillance when surfing the internet or sending messages.

- 6%, or 61 apps, pertain to Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Tibet news publications, travel guides, and language learning apps.

- 5%, or 48 apps, relate to cryptocurrencies, including exchanges that have been banned in China since 2017.

- 3%, or 31 apps, are focused on religion, specifically Tibetan Buddhism, Falun Gong, Christianity, and Islam.

- 3%, or 26 apps, target the LGBTQ community, including dating applications and chat forums.

In addition to these politically sensitive applications, other apps missing from Apple’s China App story include:

- 786 mobile gaming applications.

- 157 porn or gambling applications.

- 1,350 other apps not covered by the categories above

Please contact TTP for a complete list of apps identified in this report.